|

Isaac Henry Tate By Steven R. Butler, Ph.D. Isaac H. Tate in the Civil War, Part Three: 1864 It was not only "one of the hardest winters that had been seen in many years," recalled Oates, but also the Federals were determined "to drive Longstreet out of Tennessee." It would not be easy. In January 1864, when the General learned that "Union troops were concentrating in the neighborhood of Dandridge for the purpose of a forward movement," he "took the initiative and concentrated enough of his troops to repulse and drive back theirs, which ended that enterprise." Although Longstreet's men "were frequently disturbed and called out," remembered Oates, "no battle was fought except skirmishes with the cavalry." At length, the General "moved his force east in the direction of Greenville to Bull's Gap, a good defensive position and more convenient to supplies." Here, a "shoe shop was improvised" owing to the fact that a large number of Longstreet's men "were barefooted and the War Department in Richmond was unable to furnish shoes in sufficient quantity." When finished leather quickly ran out, "recourse was had to raw hides, just as they came off the beeves." Moccasins made with "the hairy side next to the foot," wrote Oates, were credited with saving "many men from having frost-bitten feet." Finally, in "camps in the neighborhood of Bull's Gap the army was made as comfortable as practicable under the circumstances." As many men as could get a furlough "went home, if only for a few days, that winter." Whether or not my great-grandfather was able to go home at this time is unknown but in view of the fact that a large Union force was in possession of Southeastern Tennessee and Northwestern Georgia at this time, it seems incredible that any of the Alabama men could have got through safely, although apparently some did so. "Early in March 1864," remembered Colonel Oates, after recovering from his wound he returned to the Fifteenth Alabama "in winter quarters between Greenville and Morristown at Bull's Gap, East Tennessee," where he discovered that the regiment "was under the command of a captain, Lieutenant-Colonel Feagin still being in prison and Major Lowther at home." Oates found his unit "in poor condition." Consequently, he "went to work at once to get it up to its former high state of efficiency." He was apparently pleased that in view of his men "being old veterans, it did not require any great amount of effort to put them in fighting trim" again. In his reminiscences, Oates devotes a great deal of space to writing about the enmity that existed between General Longstreet, their corps commander, and General Law, their brigade commander, and explains how the ill-feeling between the two men nearly led to the Fifteenth Alabama regiment being transferred to a different division and left "in East Tennessee, just where none of us desired to be left." However, in spite of Longstreet's efforts to "punish" General Law, who during the winter he had caused to be arrested, the Confederate War Department in Richmond overrode the corps commander's wishes and after denying Longstreet's demand for a court martial, released Law and ordered his brigade, which included the Fifteenth Alabama, "back to the old division [Hood's], which was then in Virginia." The Battle of the Wilderness

Unfortunately, the Alabamians' corps commander was "brim-full of malice" and after "Law arrived with his brigade at Cobham's Station, between Charlottesville and Gordonsville, Va., within four miles of the latter place, Longstreet arrested him again and ordered him away from his brigade to Gordonsville to await his trial." During this time, Oates remembered, "General Lee reviewed the troops" while accompanied by his daughter, "Miss Mildred," who was "admire by the soldiers for her graceful horseback riding." While camped here, many of the regiment's "sick and wounded who had recovered came to us." It was a fine spring, Oates recollected, marked by good weather. "On the 3rd of May," the Colonel remembered, "we marched to and a little south of Gordonsville and camped." When each regiment of the brigade marched past General Law, "who stood in front of his tent" to watch them pass, the men "cheered him" and Oates stopped to confer with his old friend and commander, providing him with legal advice that enabled Law to be released from arrest in time to take part in the Battle of Spotsylvania on May 12, 1864. In his postwar reminiscences, Oates explains how after President Lincoln had given General Grant command of the 150,000-man-strong Army of the Potomac in early 1864, he [Grant] commenced "a great campaign," the aim of which was to destroy Lee's army and capture Richmond, the Confederate capital. To withstand this effort, Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia consisted of only 54,000 men, a number that included Law's brigade and the Fifteenth Alabama Regiment.

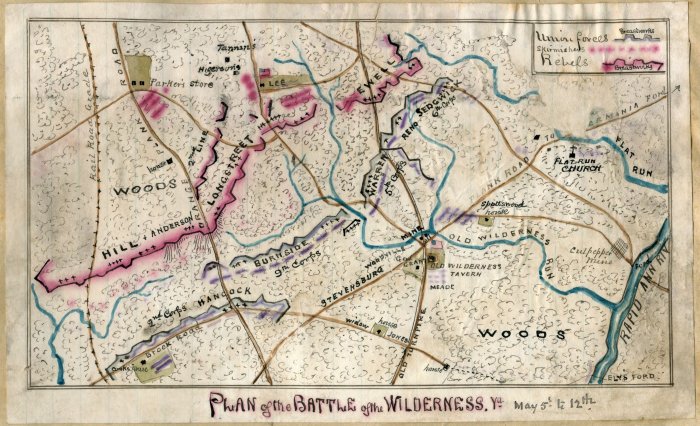

Lee's object, remembered Oates, "was to have Longstreet turn Grant's left flank and attack him in the rear, but he was too slow." Longstreet "put his two divisions in bivouac on the night of the 5th just opposite Hill's right but more than six miles away." When Lee realized that "Hill's troops could not withstand the assaults of the next morning which he anticipated from [Union General] Hancock's veteran corps of 30,000 which confronted them," he [Lee], ordered Longstreet to march through the woods that night over the Plank Road to the support of Hill." It was "about 2 o'clock A.M. on the morning of the 6th," Oates recalled, when the Fifteenth Alabama and the rest of Law's brigade "began to move." However, he added, they "progressed so slowly along the devious neighborhood road that was daylight when the head of the column reached the Plank Road, about two miles in the rear of where the fighting ceased the previous evening and where, just at this moment, it recommenced with great fury." While quick marching "to the front," remembered Oates, "we passed quite a number of wounded Confederates lying by the side of the road," including a number of generals. Here is how the Colonel remembered what happened next:

The dense woods that Colonel Oates remembered was called the "Wilderness," a "jungle-like stretch of second-growth timber and isolated farms" that "was a bad place for a fight," according to Civil War historian Bruce Catton, who also wrote:

Having rejoined "their comrades and beloved commander [Lee], after a separation of eight months, Law's brigade, which was then led by General W. F. Perry (owing to General Law being under arrest), "rose with the emergency" and while announcing to retreating troops "that they were 'Longstreet's boys,' called on their demoralized comrades to "come back" to the fight "and aid them in beating the enemy." General Perry later wrote: "Their stern resolution rose into enthusiasm when a retreating soldiers shouted, 'Courage boys; Longstreet's men are driving them like sheep!'" Here is how Perry described what happened next, after General Lee had greeted the Alabama men and they formed on the left of the Plank road "in what seemed like an old field, containing thirty acres or more":

General Perry added Colonel Oates' postwar report to him:

The Battle of the Wilderness, in which Grant's Army of the Potomac lost more than 17,000 men, resulted in a narrow victory for the Confederacy It also signaled the end of the war for my nineteen-year old great-grandfather, Isaac Henry Tate, who was one of the eleven men that Colonel Oates reported wounded. General Longstreet was also among the wounded at the Wilderness. Called "Old Peter" or "Bulldog" by his men, Longstreet was described by one soldier as "a tower of strength." Unlike Longstreet, who recovered in five months from the "gaping wounds in the neck and arms" that left "his right arm semi-paralyzed," my great-grandfather remained in an army hospital (precisely where is unknown but probably Richmond) through October 1864, recuperating from a shot to his scrotum, almost certainly fired by one of the retreating New York soldiers during the Fifteenth Alabama's assault on the Federals' position in the woods. In response to an inquiry made by the Texas Commissioner of Pensions, the United States War Department reported in March 1915 that after November 21, 1864, when Pvt. Isaac H. Tate was reported "absent without leave," no further record of him could be found, although the cover letter added: "It is deemed proper to add that the collection of Confederate Records...is far from complete." For a long time, based on this incomplete information, I speculated that my great-grandfather had become a deserter. It was certainly not unlikely. By the end of 1864, it had become apparent to many Southerners that the war, for them, was lost. Consequently, large numbers of Confederate soldiers, either wounded or simply war-weary and disgusted, went home. As it turns out, I was barking up the wrong tree. I have since discovered a "new" document, a Confederate States pay voucher dated December 3, 1864 at Columbus, Georgia, which suggests that my great-grandfather was either discharged from the army on account of disability (owing to his wound) or sent home to recover, during which time the war ended on April 9, 1865 at Appomattox Courthouse, Virginia with the formal surrender of the Confederate Army by General Robert E. Lee to Federal General Ulysses S. Grant. An army paymaster, A. B. Ragan, signed the voucher, which my great-grandfather also signed, acknowledging receipt of $115.13, in Confederate currency of course, for back pay from September 1, 1863 through June 30, 1864, at a rate of $11 per month. Why he was not paid through November or December is uncertain. In any event, it now seems clear that he was not a deserter as I had previously speculated might be the case. From all appearances, Isaac's brother James Tate remained on duty with the Fifteenth Alabama Regiment until the very end of the war, at which time the two brothers were reunited at their father's home in Russell County. Continue to: Isaac H. Tate's Postwar Life Photo of Plank Road (above) by author. Picture of Robert E. Lee (above) courtesy Library of Congress.

This website copyright © 1996-2011 by Steven R. Butler, Ph.D. All rights reserved. |

On May 4, Oates remembered, "Grant, with this immense force, crossed the Rapidan River and began his advance on Richmond." That very same day, Grant's army was attacked by Confederate troops led by General Ewell and on the 5th, "A. P. Hill's corps came into action…on Ewell's right, extending the line of battle at right angles from the river to the Plank Road in the Wilderness." Here, "the battle raged all day, while Longstreet, with Hood's old division, then Field's, and McLaws's old division, then commanded by Kershaw, was marching down the Catharpin Road, which ran parallel with and at a mean distance of about six miles from and south of the Plank Road."

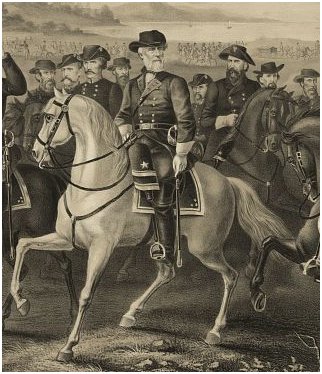

On May 4, Oates remembered, "Grant, with this immense force, crossed the Rapidan River and began his advance on Richmond." That very same day, Grant's army was attacked by Confederate troops led by General Ewell and on the 5th, "A. P. Hill's corps came into action…on Ewell's right, extending the line of battle at right angles from the river to the Plank Road in the Wilderness." Here, "the battle raged all day, while Longstreet, with Hood's old division, then Field's, and McLaws's old division, then commanded by Kershaw, was marching down the Catharpin Road, which ran parallel with and at a mean distance of about six miles from and south of the Plank Road." Longstreet's column reached the scene of the action none too soon. Hancock was just then turning Hill's right and driving his men from their position, although they were manfully contesting every inch of ground. Anderson's Georgians was the first brigade of Field's division to engage the enemy. Benning's and the Texas Brigade got into action next on the right or south side of the Plank Road, and were temporarily repulsed. We met General Benning, brought out on a litter severely wounded. Colonel Perry then formed Law's brigade, as it came up double quick, to the left of the Plank Road with the Fourth Alabama's right resting upon it and the Fifteenth on the left of the brigade and of the line. To reach our position we had to pass within a few feet of General Lee. He sat his fine gray horse "Traveler," with the cape of black cloak around his shoulders, his face flushed and full of animation. The balls were flying around him from two directions. His eyes were on the fight then going on south of the Plank Road between Kershaw's division and the flanking column of the enemy. He had just returned from attempting to lead the Texas Brigade in a second charge, when those gallant men and their officers refused to allow him to do so. My friend, Col. Van H. Manning, of the Third Arkansas, then in command of the brigade, did that himself, fell severely wounded while leading the charge, and was taken prisoner. A group of General Lee's staff were on their horses just in rear of him. He turned in his saddle and called to his chief of staff in a most vigorous tone, while pointing with his finger across the road, and said: "Send an active young officer down there." I thought him at that moment the grandest specimen of manhood I ever beheld. He looked as though he ought to have been and was the monarch of the world. He glanced his eyes down on the "ragged rebels" as they filed past around him in quick time to their place in line and inquired, "What troops are these?" And was answered by some private in the Fifteenth, "Law's Alabamians!" He exclaimed in a strong voice, "God bless the Alabamians!" The men cheered and went into line with a whoop. The advance began. It was about two hundred and fifty yards from my left to a dense woods right opposite. From that, as we advanced, came a flank fire, which the one in front made our position a critical one.

Longstreet's column reached the scene of the action none too soon. Hancock was just then turning Hill's right and driving his men from their position, although they were manfully contesting every inch of ground. Anderson's Georgians was the first brigade of Field's division to engage the enemy. Benning's and the Texas Brigade got into action next on the right or south side of the Plank Road, and were temporarily repulsed. We met General Benning, brought out on a litter severely wounded. Colonel Perry then formed Law's brigade, as it came up double quick, to the left of the Plank Road with the Fourth Alabama's right resting upon it and the Fifteenth on the left of the brigade and of the line. To reach our position we had to pass within a few feet of General Lee. He sat his fine gray horse "Traveler," with the cape of black cloak around his shoulders, his face flushed and full of animation. The balls were flying around him from two directions. His eyes were on the fight then going on south of the Plank Road between Kershaw's division and the flanking column of the enemy. He had just returned from attempting to lead the Texas Brigade in a second charge, when those gallant men and their officers refused to allow him to do so. My friend, Col. Van H. Manning, of the Third Arkansas, then in command of the brigade, did that himself, fell severely wounded while leading the charge, and was taken prisoner. A group of General Lee's staff were on their horses just in rear of him. He turned in his saddle and called to his chief of staff in a most vigorous tone, while pointing with his finger across the road, and said: "Send an active young officer down there." I thought him at that moment the grandest specimen of manhood I ever beheld. He looked as though he ought to have been and was the monarch of the world. He glanced his eyes down on the "ragged rebels" as they filed past around him in quick time to their place in line and inquired, "What troops are these?" And was answered by some private in the Fifteenth, "Law's Alabamians!" He exclaimed in a strong voice, "God bless the Alabamians!" The men cheered and went into line with a whoop. The advance began. It was about two hundred and fifty yards from my left to a dense woods right opposite. From that, as we advanced, came a flank fire, which the one in front made our position a critical one.