|

Alfred Butler in the Mexican War By Steven R. Butler, Ph.D.

As the news of Zachary Taylor's victories at Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma on May 8 and 9 spread across the land, the states of the Mississippi Valley were the first ones asked to supply troops. Alabama governor Joshua L. Martin immediately issued a call for men to come forward to fulfill President Polk's requisition "for 'one regiment of volunteer Infantry or Riflemen' to serve for the term of twelve months."3 Certainly, it was not difficult to find eager recruits willing to serve. One historian has noted that the war with Mexico "was regarded as a frolic and Mexicans were spoken of as cowards. Recruiting officers spoke glowingly of the beauty of the Mexican girls, the chances for plunder, the loveliness of the scenery, and pictured the soldier's life as one long picnic."4 Perhaps this attitude accounts for why Greene County, Alabama produced not just one, but two companies, both of which were organized during the latter half of May 1846. One, adopting the name "Eutaw Rangers," was raised by Stephen F. Hale and Sydenham Moore, prominent Eutaw lawyers. The other company was raised by Andrew Pickens of Greensboro (located in present-day Hale County), who led a band of eager recruits styling themselves simply the "Greensboro Volunteers." Of all the regiment's companies, these were the only two to leave home wearing any kind of uniform. The latter, according to one of the Eutaw men, "wore a green worsted frock suit," while the former sported "cottonade suits made by the ladies, with straw hats."5

The building in the photo to the right, still standing in Eutaw's courthouse square, is where Judge Moore enlisted the Eutaw Rangers in 1846. Alfred Butler, about twenty-two years of age at the time of his enlistment was among the privates in Captain Moore's company. His discharge certificate reveals that at the time of his enlistment he was a carpenter by trade, was 5 feet, 9 inches tall, and had a light complexion, blue eyes, and light hair.8 This description is especially valuable in that no portrait or photograph of him is known to exist. Papers included in Alfred Butler's Mexican War bounty land file also provide evidence that he lacked an education. Unable even to write his own name, he marked all documents he was required to sign with an "X," as a substitute for his signature. This was not exceptional. A great many nineteenth century Americans were equally illiterate. Twenty-year old Levin Butler was another volunteer in Captain Moore's company.9 Owing to the fact that during this period, there were two other individuals, both residing in Bertie County, North Carolina, who also bore the name Levin Butler10 and furthermore, because Bertie County was Alfred Butler's birthplace I am inclined to think that the Levin Butler who served in Moore's company was Alfred Butler's brother or perhaps his cousin, although to date (2015) no evidence has been found to confirm it. Between June 8 and 19, the various companies of what became known as the First Alabama Regiment of Volunteers were mustered into federal service at Mobile by Brigadier General Walter Smith of the United States Army.11 On May 30, 1846, The Daily Picayune of New Orleans reported the arrival in Mobile of three of the first companies raised:

The same edition also noted that, "The citizens of Mobile are raising a fund for the purpose of providing Captain Todd's artillery company with a uniform suitable for their campaign."13 Whether the citizens of Mobile were successful in fulfilling their pledge is unknown. Because of his illiteracy Alfred Butler left no written account of his service in the war with Mexico, nor did his widow or any of his children, so far as we know, ever make a record of anything he may have told them. Fortunately, a fellow soldier, Stephen F. Nunnalee kept a journal and also, some sixty years after the war, wrote a reminiscence of his service in Moore's Company. Captain Moore likewise kept a journal and also wrote letters that have survived. It is to these two men therefore, as well as to newspapers and the official records of the United States Army that we have been compelled to turn for our knowledge of what Alfred Butler and his comrades experienced during the twelve months they spent in Texas and Mexico. "Everything was full of excitement," Stephen Nunnalee recalled, when, on June 1, 1846, Moore's Company boarded a steamboat called the "Noxubee, "commanded by Capt. Kinney, at Finche's Ferry [also called "Three Mile Landing"], amid the waving of hats, handkerchiefs, and the huzzas of a large concourse of citizens."14 Nunnalee also remembered that "Col. John W. Womack and Hilliard Judge made farewell speeches and Captain Moore and Lieut. Hale responded on behalf of the company. The company received a banner and also a farewell in town. Miss Sara Inges presented the flag, which was accepted by Wm. A. Bell."15

From Greene County the "Eutaw Rangers" steamed down the Black Warrior and Tombigbee Rivers to Mobile, where they arrived on June 8. There, they "were given a reception...and in a day or so...were marched out to Camp on Yellow Creek, 4 or 5 miles N.W. of the City."61 On June 27, 1846 an election was held in the volunteer camp which resulted in John R. Coffey of Jackson County being chosen Colonel of the regiment. Elected on the same day were Richard G. Earle of Calhoun County, Lieutenant Colonel, and Goode Bryan of Tallapoosa County, Major. Later, on July 6, following the regiment's arrival in Texas, Hugh P. Watson of Talladega County was appointed Adjutant.17 Stephen Nunnalee was displeased with the choice of Coffey as colonel of the regiment, preferring his own captain. Coffey, he recalled, "was a good, and clever man, but had no military gifts. Had [Sydenham] Moore been elected, we doubtless would have seen some hard fighting, for he was a man of ambitious and military bearing." Nunnalee also remembered that as a consequence of Coffey being "unmilitary like in voice, and general make up," the men became openly disrespectful of him, calling their commander "John," rather than addressing him by his military title.18 In all, the First Alabama Regiment of Volunteers consisted of nine companies, totaling 900 men. The captains of each company were: Company A, Andrew L. Pickens of Greene County; Company B, Zachariah Thomason of DeKalb County; Company C, William G. Coleman of Perry County; Company D, Sydenham Moore of Greene County; Company E, Jacob D. Shelley; Company F, Richard W. Jones of Jackson County; Company G, Drury P. Baldwin for Pike, Baldwin and other counties; Company H, John B. Youngblood; and Company I, Eli T. Smith of Calhoun County.19 On June 29, 1846, at Mobile, all but two companies of the regiment boarded the steamer Fashion for the short sea voyage across the Gulf of Mexico to Texas (with those left behind to follow as soon as possible). There, Zachary Taylor's forces were being concentrated in camps located in the lower Rio Grande Valley, between the mouth of the river and Matamoros, about twenty miles inland. The regiment's arrival on Independence Day is confirmed by a letter, written by Colonel Coffey to Captain William W. S. Bliss, Zachary Taylor's adjutant:

The regiment, described by The Matamoros Reveille as "as noble a set of men as ever need shoulder a gun,"21 arrived off the coast of Texas, according to the reminiscences of Stephen F. Nunnalee, "about 10 A.M. July 4th., as hot a day as I almost ever experienced." Nunnalee also recalled that he "had been detailed to help unload the Regimental Equipage," a job which, for some reason left unstated, resulted in he and his comrades coming "near to having a serious row with the boat hands."22 Initially, the regiment set up camp on Brazos Island, a sandy, windswept piece of land separated from the southern end of Padre Island by the narrow Brazos Santiago Pass.23 In his reminiscences, Nunnalee recalled that "few if any tents [were] erected that day [July 4], but the men scattered extensively over the island, which was covered with musquite [sic] grass and brackish lagoons. Not a tree was to be seen, except in the distance."24

On the very day they arrived in Texas, the regiment lost three men in an unfortunate accident. The Matamoros Reveille, dated July 15, 1846, carried the story:

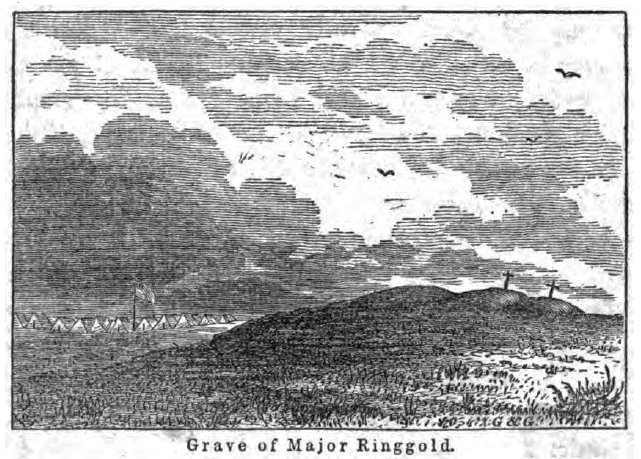

Fortunately for Stephen Nunnalee and some friends, a trip by boat across the calmer waters of the Laguna Madre, for the purpose of visiting nearby Point Isabel, was made without incident. There, General Zachary Taylor had set up a fortified supply depot named "Fort Polk." Nunnalee recalled that while there, he "visited the grave of Maj. Samuel Ringgold, enclosed with Mexican muskets," adding that Ringgold "was mortally wounded on the 8th of May, in the battle of Palo Alto, and died on the 11th following."26

With the exception of the surf bathing, which Nunnalee pronounced as "fine," camp life for the Alabamians on Brazos Island quickly became unbearable, as the former soldier later recalled:

Fortunately for the suffering Alabamians, permission was granted to move "to the ridges or higher land, a few miles below Matamoras," where, upon arrival, recalled Nunnalee, they "pitched camp to the right."28 A volunteer of the Maryland and Washington Regiment, in his diary entry for July 20, 1846, confirms, in complimentary terms, the Alabamians' arrival on that date:

The high ground where the First Alabama set up their tents was a long, narrow rise of land located on the north side of the Rio Grande, identified on modern-day maps as the Loma de Estrella (Hill of Stars). The site, covered with tall grass, prickly-pear cactus, Spanish dagger, and other thorny plants, had been given the name "Camp Belknap" in honor of Lt. Colonel William G. Belknap, one of Zachary Taylor's regular army officers. Across the nearby Rio Grande, "as muddy as...the Red River," commented Nunnalee, lay the little Mexican village of Burita. The river, as well as being muddy, was also noted for its crookedness, causing one Alabamian to comment humorously that "he had seen a crow fly from the top of a tree, follow up the course of the river for fifteen minutes, then light; and it lit on the same tree it had started from."30

Nunnalee remembered that the Alabama regiment made its way "up to the ridges or higher land, a few miles below Matamoras, and pitched camp to the right, about "a mile from the river, from whence [we] had to lug water in camp kettles, although a beautiful lagoon lay just at the foot of the ridge on which our regiment was camped."31 Unfortunately, the "beautiful lagoon" Nunnalee remembered was in reality both shallow and brackish, being the lower end of the Laguna Madre-that long, narrow body of salt water which separates both Brazos and Padre Islands from the Texas mainland. Nunnalee also recalled "The Kentucky regiment was on another ridge to our left, facing the river, and the Georgia Regiment to our right and rear, on another ridge.32

During the summer of 1846, Camp Belknap was home to some 8,000 soldiers,33 making it the single largest U.S. volunteer encampment of the Mexican War. In addition to the men from Alabama, volunteers from Kentucky, Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Maryland and the District of Columbia, Georgia, and Tennessee all pitched their tents at Belknap,34 together enduring the heat of the South Texas summer, as well as bites, pricks and cuts inflicted by the region's exotic flora and fauna, prompting the universal complaint that "all the plants have thorns and all the insects have horns."35 One of the Indiana men, Benjamin Franklin Scribner, in a letter addressed to his folks back home, included this description of Camp Belknap:

Burita, the town opposite Camp Belknap, as described by Samuel C. Reid, indicated it was nothing much to look at either:

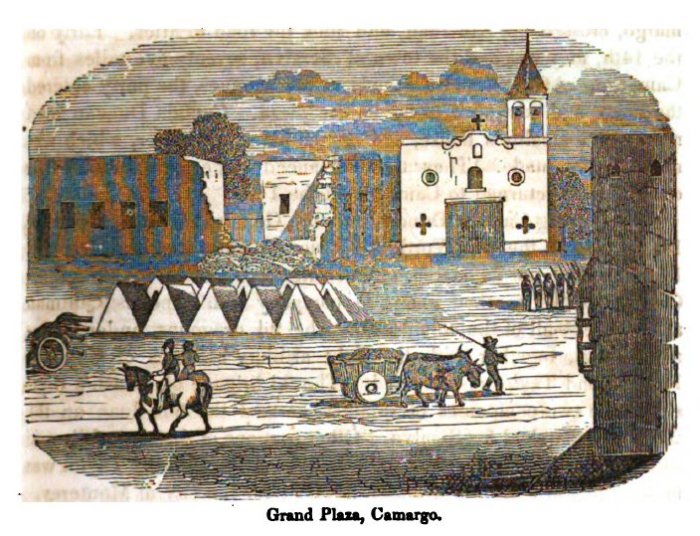

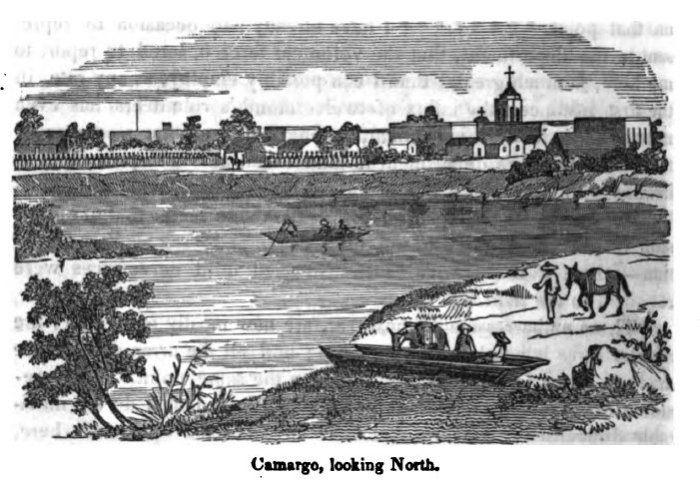

Stephen Nunnalee later recalled that he and his fellow-soldiers "enjoyed the change [from Brazos Island to Camp Belknap] very much for a week or two." But, he also remembered, "the water and only hard tack and bacon soon caused almost an epidemic of diarrhoea, and many deaths occurred." As a result, Nunnalee wrote, "discontent and homesickness" pervaded the camp, and "no attempt [was made] to instruct the men in military exercises." During this time, Nunnalee recalled, he and his comrades "discovered by putting a few slices of cactus leaf in our water that it soon became clear and palatable." But, he wrote, "sickness continued, little attention being paid to sanitary conditions."38 Their stay at Camp Belknap, however, was brief. Before the end of August, the Alabamians, along with most of the other volunteer and regular troops under Taylor, were moved upriver to a small Mexican settlement called Camargo, leaving small garrisons behind at Point Isabel, Matamoros, and Fort Brown. At Camargo, Taylor planned to concentrate the bulk of his forces in preparation for an attack on Monterey. Some regiments traveled upriver by steamboat while others marched overland. The Alabamians, according to Nunnalee, made the journey aboard the Colonel Cross,39 a steamboat named for an American army officer murdered by Mexican guerillas in April of that year.40 Orders issued at Camargo by Captain Bliss on August 19, 1846 directed the Alabamians to join the brigade under command of General John A. Quitman. Along with the Mississippi and Georgia regiments and the battalion of Maryland and District of Columbia volunteers, this group was designated the 3rd brigade of the 2nd division. Included in the same special orders (No. 126) assigning them to Quitman's brigade, the ordnance department was directed to "replace the arms of the 1st regiment Alabama volunteers, lately pronounced by a board of its officers as unserviceable, by as many serviceable arms as it is practicable to furnish." Cartridge boxes and bayonet scabbards, if deemed unserviceable, were replaced as well,41 and at some point during their twelve months' service, regular army uniforms were also supplied. It is unclear however, whether the entire regiment or just Moore's company received new uniforms. In either event, Nunnalee remembered, they were "navy blue Suits, with brass buttons and Caps."42 The Alabama regiment arrived at Camargo on September 1, 1846. Although it made a change from rattlesnake and insect-infested Camp Belknap, Camargo was not much improvement. One Texas volunteer, William A. Droddy, wrote in his diary:

Doubtless, Camargo was possibly the worse place for a major encampment of troops that Taylor could have chosen. A description of the town, found in The Story of the Mexican War by Robert Selph Henry, echoes the words of the soldiers who had to suffer its inhospitable nature:

Indeed, during the entire twelve months they spent in Texas and Mexico the First Alabama Regiment lost but one man to enemy bullets while some 150 succumbed to disease and about 200 had to be discharged due to illness. In all likelihood, the majority of the deaths occurred at Camargo. There were, according to the regimental report for September 1846, 15 deaths that month alone, along with a significant number of sickness-related discharges. Additionally, there were 192 men reported sick who were not discharged that month, a number which included 2 captains, 7 lieutenants and 26 non-commissioned officers.45 How many of the men, separated from service because of illness, died on the way home, or after reaching there, is unknown. Equally unknown is the number of men who died at an early age from a recurrence of some illness originally contracted in Mexico. The Tennessee volunteers seem to have suffered even more so than the Alabama men. In October, Niles' National Register reported:

The paper also remarked that although there were more patients in the hospital at Matamoros, the mortality rate was three times higher at Camargo.47 The camp of the Alabama volunteers, Stephen Nunnalee recalled, was located "on the San Juan, about a mile above Camargo on a high level or plateau." There, he wrote, a "camp and parade ground were cleared off, and some attention was given to drill and guard duty." But, commented the former soldier: "Compared to the military science of the present day, the efforts were farsical in the extreme." The problem, Nunnalee thought, lay with their officers. If Coffey was unmilitary in voice and manner, few of the regiment's other officers were an improvement. "Col. Earle," wrote Nunnalee, "was all 'fire and tow,' and wanted everything done to a niceity, but he lacked military skill and knowledge." And while Captain R. M. Jones, "often laughed in his sleeve at some of the rare commands and general mixing up in the execution of maneuvers," Major Goode Bryan, a graduate of West Point "knew all about it, but seemed disgusted at the idea of ever seeing this material worked up into shape as 'food for gun powder.'" Yet, recalled the ex-soldier, "all improved in the course of time."48 Nunnalee also remembered Brevet Major Robert Fenner, a veteran of the War of 1812, who in June 1846 had been commissioned Assistant Commissary for subsistence for the First Alabama regiment:

Later in the year Fenner became so ill he was furloughed back to the United States. During the early months of 1847 he briefly recovered, afterwards feeling well enough to sit for a daguerreotype portrait with his wife Lucy. But in September of that same year the Major suffered a recurrence of the illness (probably amoebic dysentery) he had contracted in Mexico. His condition complicated by malaria, then rampant in New Orleans, he died.50

On August 17 the first detachment of troops selected to participate in the attack on Monterey marched out of Camargo. Unfortunately, a lack of supplies and transportation, the result of delays by the Quartermaster's Department in New Orleans, left Taylor no choice but to leave behind a large number of men to garrison Camargo, brigaded under Gen. Gideon J. Pillow.53 When the Alabama soldiers learned they were to be among the garrison troops, they found it difficult to hide their disappointment. Recalled former private Nunnalee:

Shortly afterwards, Colonel Coffey was forced to deal with another difficulty, one which led him to seek the advice of his immediate superior, General Gideon Pillow. A letter, which Coffey wrote to Pillow, describes the problem:

Whether or not General Pillow rendered any assistance to Colonel Coffey is unknown. No record has been found of his reply, if any. Hopefully, the problem was resolved. Following the departure of the last detachment for Monterey, Company D-the so-called "Eutaw Rangers," were assigned the task of guarding the Quartermaster's depot at Camargo, located opposite the Alabama regiment's encampment, on the other side of the San Juan River. There, according to former-Private Nunnalee, there were a "half million dollar's worth of Army stores gathered...in charge of Captain Wm. Tecumseh Sherman."56 However, although the details of his recollections are generally consistent with most official records, Nunnalee was mistaken. Captain William T. Sherman, the very same who was to go on to infamy during the Civil War as the man who left a swath of destruction in Georgia, did participate in the Mexican War, but not in Northern Mexico. That Captain Sherman, an officer of the 3rd Artillery regiment, saw service only in California. The Captain Sherman with whom Nunnalee confused him was Captain Thomas W. Sherman, who coincidentally, was also attached to the 3rd Artillery.57 One day, the former volunteer recalled, some excitement broke out in camp which led Nunnalee to conclude that the man he later assumed was the same one whose actions during the Civil War earned him the acrimony of the South, was something of a coward: There were frequent reports that the Mexicans were lurking in the neighborhood for the purpose of capturing the Post. This resulted in an amusing "false alarm." Firing began across the river (on the encampment side), by whom we sentinels at the Post rightly judged a company of Texas cavalry. That raised a hellow-bellow in our regiment. We could hear the perfect Babel of inquiries and exclamations, such as "where's my hat," "where's my shoes," "where's my gun"-"my ram-rod is gone." "The Colonel's mare is on fire," etc. (They had been burning brush heaps). Amid this confusion and excitement, Capt. W. T. Sherman, visited the Post Sentinels, exhorting them, (with evident fear and alarm) to "keep cool"-"don't be scared," "there are millions of dollars worth of supplies confided to our keeping"-said all this to the writer who replied, "Why, Captain, if I was half as badly frightened as you seem to be, I would take to the woods."58 Not long after this incident, wrote Nunnalee, "a wagon and pack train arrived and the stores were shipped to General Taylor's army, who had won a glorious victory at Monterey," and the "Eutaw Rangers" rejoined their regiment.59 Captain Thomas W. Sherman, perhaps shaken by his experience, also rejoined his outfit, leaving the greatly reduced quartermaster's stores in charge of Captain Franklin Smith of the Mississippi Volunteers.60 Captain Smith, who kept a diary of his service in Mexico, wrote on September 27 that as a result of the news of Taylor's victory at Monterey, the men who formed the garrison at Camargo "were variously occupied some crying and getting drunk, some rejoicing and getting drunk, some writing letters-few thought about sleep."61 The next day, he wrote:

Afterwards, from the end of September until late November, the Alabamians found themselves with little do except attend the sick and bury the dead. With "no prospect of being ordered to the front," morale suffered. The men not only became disobedient but at night, seeking excitement, said Nunnalee, some would slip away from camp "and roam at will through the country and depredate upon private rights."63 It was a dangerous business. Not long after arrival at Camargo, two of the Alabama men had wandered away from camp and been found with their throats slit.64 Later, when the Mexicans apparently retaliated for the after-dark forays by murdering two Tennessee volunteers, "orders were issued that no permits were [to be] given and roll calls should be had several times during the day." Although aimed both at keeping the soldiers in line as well as saving their lives, these orders were unpopular. Recalled Nunnalee: "When the drum for roll calls [was sounded] a general howl went up in all the regiments (more for fun than anything else). Stringent orders were issued against this which made things worse."65 One day, Nunnalee recalled, Generals Pillow and Patterson had the Alabama regiment drawn up in formation, during which Pillow "made a pompous, indiscreet speech full of vanity and reproaches." Afterwards, as the men were being dismissed, one wag, whom Nunnalee identified as his company's "pet," or "mascot," shouted out sarcastically, "Three cheers for Corporal Pillow!"-an act which set off a round of "howling, cat-calls and assbraying...in at least two regiments-la. & Tenn." Infuriated by this brazen display of impertinence, General Patterson, "on his beautiful little black mare, made a dash for Col. Coffey's tent" where, after having it pointed out to him by the very man who'd started the commotion, he proceeded to give the Alabama Colonel "a very fervid curtain lecture, which he took very meekly." Patterson "then dashed off and rejoined Pillow," but "as they cleared the line of sentinels, the Pet called for-Three cheers for Sergeant Patterson, and the serenade was encored."66 Continue to: Alfred Butler in the Mexican War, Part Two NOTES 1Niles' National Register, Baltimore, Maryland, Vol. 70, Whole No. 1807, May 16, 1846, 166. 2George Minot, ed., The Statues at Large of the United States of America from December 1, 1845 to March 3, 1851, Vol. IX (Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1851), 9-10. 3Mobile Register & Journal, May 16, 1846. 4Wellington Vandiver, "Pioneer Talladega, Its Minutes and Memories," Alabama Historical Quarterly, Vol. 16, No. 1, Spring 1954, 83. 5Nunnalee, Stephen F. "Letter to Dr. W. S. Wyman from S. F. Nunnalee," Alabama Historical Quarterly, Vol. 19, Nos. 3 & 4, Fall & Winter 1957, 417. The original of this letter, giving a brief anecdotal history of Company D, First Alabama Regiment of Volunteers, is in the Military Records Division, Mexican War Correspondence, Alabama Department of Archives and History. Although the letter was invaluable to this author for the purpose of reconstructing the history of this regiment, it contains several factual errors, primarily names and dates. Obviously, these mistakes are the result of the letter being written some six decades after the events occurred which it describes. 6Thomas McAdory Owen, History of Alabama and Dictionary of Alabama Biography, Volume IV (Chicago: The S. J. Clarke Publishing Company, 1921), 1235-6. 7Nunnalee, 417. 8Discharge certificate for Alfred Butler, Mexican War Bounty Land File No. 4908-160-47, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C. 9Levin Butler, Mexican War military service record, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C. 10Seventh Census of the United States, 1850: Bertie County, North Carolina; Roll: M432-621; Page: 18B; Image:41; (National Archives Microfilm Publication M432, 1009 rolls); Records of the Bureau of the Census, Record Group 29; National Archives, Washington, D.C. 11Muster rolls of the First Regiment of Alabama Volunteers, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C. 12Daily Picayune, New Orleans, Louisiana, May 30, 1846. 13Ibid. 14Steven R. Butler, ed., The Mexican War Letters and Journal of Capt. Sydenham Moore and the Mexican War Journal of Pvt. Stephen F. Nunnalee, Company D, First Regiment of Alabama Volunteers (Richardson, Texas: Descendants of Mexican War Veterans, 1998), 79; Nunnalee, 416. 15Nunnalee, 416. 16Ibid., 417. 17Muster roll of the Field and Staff and of the Commissioned Staff or the Alabama Regiment of the Alabama Volunteers into the service of the United States by the President, from the 28th day of Feb. to the 30th day of April 1847; Military Records Division, Alabama Department of Archives and History, Montgomery, Alabama. 18Ibid., 417 & 420. 19Officers of the [Alabama] Regiment, Present and Absent, accounted for, Transfers from the Regiment, Resignations, Deaths, etc.; National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C. 20Niles' National Register, Baltimore, Maryland, Vol. 70, Whole No. 1815, July 11, 1846, 294; Letter from John R. Coffey, Colonel Commanding 1st Regiment Alabama Volunteers, at Brazos Santiago, to Capt. W. W. S. Bliss, Asst. Adjutant General, Matamoras, Mexico (General Taylor's encampment), dated July 4, 1846, Military Records Division, Mexican War Correspondence, Alabama Department of Archives and History, Montgomery, Alabama. Although Niles' National Register (July 11, 1846) reported that only one company was left behind at Mobile, Colonel Coffey, who accompanied the troops, states that all but two companies had arrived in Texas. It seems much more likely that Coffey's report was correct. 21Matamoros Reveille, Matamoros, Mexico, July 15, 1846, 2. 22Nunnalee, 419. 23Ibid. 24Ibid. 25Matamoros Reveille, Matamoros, Mexico, July 15, 1846, 2. 26Nunnalee, 419. 27Ibid. 28Ibid. 29John R. Kenly, Memoirs of a Maryland Volunteer, War with Mexico (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co., 1873), 45. 30Kenly, 49. 31Nunnalee, 419. 32Ibid. 33This figure is approximate, based on the muster rolls of the various volunteer units known to have camped at Belknap during the summer of 1846. 34Several different sources in addition to muster rolls confirm the presence of these troops at Camp Belknap. 35Scribner, 22. 36Ibid. 37Samuel C. Reid, Scouting Expeditions of McCulloch's Texas Rangers (Philadelphia: G. B. Zieber and Co., 1847), 20. 38Nunnalee, 419-20. 39Ibid., 420. 40Thomas Bangs Thorpe, Our Army on the Rio Grande (Philadelphia: Carey and Hart, 1846), 36-7. 4130th Congress, 1st Session, House Executive Document No. 60: Mexican War Correspondence (Washington, D.C.: Wendell & Van Benthuysen, 1848), 535. 42Nunnalee, 417. 43"Diary of William A. Droddy," Yellowed Pages, Beaumont, Texas, Southeast Texas Genealogical & Historical Society, Vol. XVIII, No. 3 (1980), 169. 44Robert Selph Henry, The Story of the Mexican War (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1950 ), 139. 45Return of the First Regiment of Alabama Volunteers Commanded by Col. Coffey, for the Month of September 1846, dated October 1, 1846 at Camargo, Mexico, Military Records Division, Alabama Department of Archives and History, Montgomery, Alabama. 46Niles' National Register, Vol. LXXI, Whole No. 1827, October 3, 1846, 67. 47Nunnalee, 419-20. 48Ibid., 420. 49Ibid. 50Francis Heitman, Historical Register of the United States Army for One Hundred Years (1779-1879) (Washington, D.C.: T. H. S. Hamersly, 1880), 263. 51Henry, 141. 52Ibid., 41-2. 53Nathan Covington Brooks, A Complete History of the Mexican War (Philadelphia: Grigg, Elliott & Co., 1849), 166. 54Nunnalee, 421. 55Letter from John R. Coffey, Col. Ala. Vols., to Brigadier General Gideon Pillow, dated September 12, 1846 at Camargo, Mexico, Military Records Division, Mexican War Correspondence, Alabama Department of Archives and History, Montgomery, Alabama. 56Nunnalee, 421. 57Hugh M. Robarts, Mexican War Veterans (Washington, D.C.: Brentanos, 1887), 16. 58Nunnalee, 421. 59Ibid. 60Joseph E. Chance, ed., The Mexican War Journal of Captain Franklin Smith (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1991), 24-25. 61Ibid., 28. 62Ibid. 63Nunnalee, 422. 64Ibid. 65Ibid., 421-2. 66Ibid., 422.

This website copyright © 1996-2015 by Steven R. Butler, Ph.D. All rights reserved. |

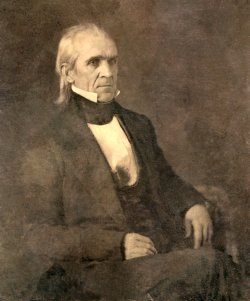

On May 11, 1846, announcing that Mexican soldiers had crossed the Rio Grande and "shed American blood on American soil," President James K. Polk (see left) urged Congress to declare war against Mexico.

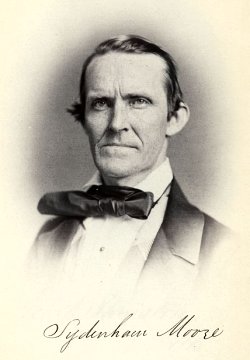

On May 11, 1846, announcing that Mexican soldiers had crossed the Rio Grande and "shed American blood on American soil," President James K. Polk (see left) urged Congress to declare war against Mexico. Sydenham Moore, elected captain of the "Eutaw Rangers," was a native of Madison County, Alabama, where he was born in 1817. As a young man he attended the state university. Following graduation, he studied law at Huntsville. In 1839 Moore set up a law practice in Eutaw. A year later he was elected county judge, a position he held until the Mexican War began. His sole military experience up to that time had been as a volunteer in Captain Otey's company during the Cherokee troubles of 1838. Moore was later elected to Congress, from which he resigned in 1861 after Alabama seceded. Although he survived the Mexican War, as colonel of the 11th Alabama Regiment, C.S.A., Moore would be killed leading his men in battle during the Civil War.

Sydenham Moore, elected captain of the "Eutaw Rangers," was a native of Madison County, Alabama, where he was born in 1817. As a young man he attended the state university. Following graduation, he studied law at Huntsville. In 1839 Moore set up a law practice in Eutaw. A year later he was elected county judge, a position he held until the Mexican War began. His sole military experience up to that time had been as a volunteer in Captain Otey's company during the Cherokee troubles of 1838. Moore was later elected to Congress, from which he resigned in 1861 after Alabama seceded. Although he survived the Mexican War, as colonel of the 11th Alabama Regiment, C.S.A., Moore would be killed leading his men in battle during the Civil War. The other officers of Company D were: Stephen F. Hale, First Lieutenant; John C. McIntyre, Second Lieutenant; and George G. Snedicor, who became Second Lieutenant when McIntyre, due to illness, resigned on Sept. 7, 1846 and returned home.

The other officers of Company D were: Stephen F. Hale, First Lieutenant; John C. McIntyre, Second Lieutenant; and George G. Snedicor, who became Second Lieutenant when McIntyre, due to illness, resigned on Sept. 7, 1846 and returned home.

On August 15, 1846, at Camargo, General Taylor (see left) held a "grand review" of his regular troops.

On August 15, 1846, at Camargo, General Taylor (see left) held a "grand review" of his regular troops.