|

The Haycraft Family

The Haycraft Family in London |

James Haycraft, Jr. |

Samuel Haycraft, Sr.

James Haycraft, Jr.

By Steven R. Butler, Ph.D.

Author's note: Because I have close personal ties to London, I was very pleasantly surprised when I learned in 1999 that I had an English ancestor who was born and raised there--although at the same time I felt a bit chagrined by the fact that he was one of "His Majesty's Seven Year Passengers," i.e. a transported convict. In 2007 and again in 2009, I took time to visit some of the sites associated with the unfortunate incident that resulted in the "transportation" of my sixth great-grandfather, James Haycraft, Jr., to America in 1744. Some of the photos I took on those occasions have been used to illustrate this essay.

In his celebrated 1869 History of Elizabethtown, Kentucky, James' grandson, Samuel Haycraft, Jr., included some biographical sketches of Hardin County's prominent early families. In regard to his own, Haycraft asserted that his grandfather was a seaman in the Royal navy who arrived in America about 1740, adding: "How he happened to stay, none living can now tell." Speculating that grandfather James either took "French leave" (i.e., deserted) or was discharged, he remarked that one way or the other his emigrant ancestor "liked the looks of the country and concluded to make it his own."1 In 1878, this version of the family's New World origins was perpetuated in a sketch about James' son, Samuel Haycraft, Sr., which was published in The Biographical Encyclopedia of Kentucky.2 However, this version is not accurate. Whether Samuel Haycraft, Jr. was truly ignorant of the actual circumstances that led to his English grandfather's arrival in America or was simply trying to protect his family's good name is uncertain. Whatever the case, it is a shame that he didn't know (or wouldn't tell) what really happened, for it is quite an interesting story.

It appears that James Haycraft, Jr. was born in London in 1719. In any event, the parish register of Saint Andrew's Church in Holborn records the christening of a child by that name on December 19th of that year. The infant's father was also named James Haycraft (or Haycroft as it was also spelled). His mother's given name was Hannah.3 Her maiden surname is unknown. Although severely damaged by German bombs during World War II, Saint Andrew's, one of several London churches designed by Sir Christopher Wren, was rebuilt and I can personally attest to the fact that it is still standing to this day at Holborn Circus, EC1 (see photo below).

St. Andrews, Holborn, where James Haycraft, Jr. was christened in 1719, was photographed by the author in 2007.

The author at St. Andrew's Church, Holborn, London, 2007.

At about the time he reached adulthood (if we accept that he was the same person whose christening is recorded in the Saint Andrew's parish register), James Haycraft met a young woman named Ann Henley or Henry. Ann would later claim that she and James were married at the town of Malden, in Kent, about 1741.4 This is curious, most of all because there is no town Malden in Kent. There is however, a town called Maldon (spelled with an "o" instead of an "e") in Essex. Perhaps the court clerk made a mistake or possibly Ann misspoke. There is also the possibility that Ann lied and that the couple's relationship was instead what is known as a "common-law" arrangement.

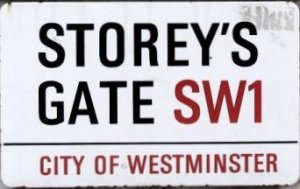

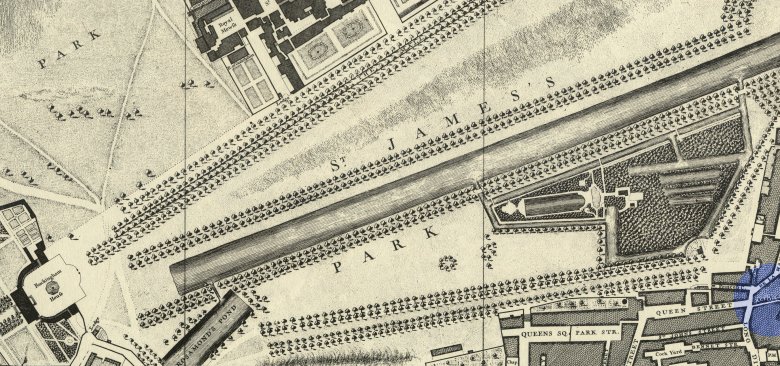

In 1744--during the reign of King George II, James Haycraft and Ann Henley were living together as man and wife in Saint Margaret's Parish, Westminster, in a dwelling located in Angel Court, Story's Gate, close by Westminster Abbey.5 Modern day visitors to London will find that Angel Court no longer exists but Story's Gate still leads to the southeast corner of Saint James' Park (see painting below), just as it did in the mid-eighteenth century. Saint Margaret's Church also still stands, immediately adjacent to Westminster Abbey, and not far from where the two young people resided. In 1744--during the reign of King George II, James Haycraft and Ann Henley were living together as man and wife in Saint Margaret's Parish, Westminster, in a dwelling located in Angel Court, Story's Gate, close by Westminster Abbey.5 Modern day visitors to London will find that Angel Court no longer exists but Story's Gate still leads to the southeast corner of Saint James' Park (see painting below), just as it did in the mid-eighteenth century. Saint Margaret's Church also still stands, immediately adjacent to Westminster Abbey, and not far from where the two young people resided.

This 1749 map of London shows that Angel Court (see blue half-circle, right), where Haycraft and Henley lived, was adjacent to St. James' Park and not far from Buckingham House (present-day Buckingham Palace). Downing Street, Horseguards Parade, the Houses of Parliament, and Westminster Abbey are also nearby.

This 1749 painting by Canaletto, titled "Old Horse Guards from St. James' Park," illustrates some of the same area shown on the above map.

At this time James Haycraft made his living as a chimney sweep. A fellow sweep, Samuel Smytheman, lived in nearby Petty France street with a young woman named Elizabeth Eaton. From all accounts, Haycraft and Smytheman met in late 1743 or early 1744 and in short order the two couples became friends.6

Life was hard for the working poor in Georgian London, particularly chimney sweeps, who were poorly paid, worked in dangerous conditions, and whose face, hands, and clothing seemed to be perpetually coated with black soot. Moreover, the work was seasonal. In order to make a living in the summer months, sweeps oftentimes "chose to be 'nightmen' engaged in emptying privies," which was not an especially pleasant task.7 Although these circumstances do not excuse what happened, they certainly go a long way toward explaining why my ancestor and his friends turned to a life of crime. Life was hard for the working poor in Georgian London, particularly chimney sweeps, who were poorly paid, worked in dangerous conditions, and whose face, hands, and clothing seemed to be perpetually coated with black soot. Moreover, the work was seasonal. In order to make a living in the summer months, sweeps oftentimes "chose to be 'nightmen' engaged in emptying privies," which was not an especially pleasant task.7 Although these circumstances do not excuse what happened, they certainly go a long way toward explaining why my ancestor and his friends turned to a life of crime.

In late March 1744, Haycraft and Smytheman decided that they would burglarize a shop owned by William and Ann Griffiths. If Smytheman's testimony can be trusted, it was not their first such "job." The location of the Griffiths' shop is uncertain but it was probably situated in Westminster where the robbers lived, or Holborn where they "fenced" the stolen goods. Smytheman later claimed that Ann Henley originally proposed the scheme whereas she said the robbery was his idea.8 In either case, it seems clear that the motive was simply to obtain far more money than either Smytheman or Haycraft could earn legally by sweeping chimneys, selling soot, or cleaning privies.

At about ten o'clock on the night of Thursday, 5 April 1744 (old style), Haycraft used a hammer to break the lock that secured the door of Griffiths' shop. Acting as lookouts, the two women waited outside in the street while their "husbands" took their time looting the shop. Apparently, no one disturbed them because it was not until after midnight that the two men finally emerged, carrying either a trunk or a sack full of penknives, metal buckles, cheap jewelry, and a variety of similar items, which they initially took to Smytheman's and Eaton's residence on Petty France.9

At about four o'clock on the morning of 6 April, Ann Griffiths later testified, she was "called up" to find "my shop broke open" and that she and her husband had been robbed. Later that day, she somehow learned that Haycraft and Smytheman had given away some of the stolen goods. This prompted the Griffiths to obtain a search warrant from a Justice Poulson.10

That same day, apparently, the youthful thieves went to Holborn, "overagainst Gray's-Inn Gate," where they first tried to sell the stolen goods to a stallholder for 20 shillings. Rejecting an offer of only 8 shillings, Eaton and Henley next approached a shopkeeper named Francis Whiting, telling him they had some hardware to sell. He agreed to meet them later in a nearby alehouse. When Whiting arrived, Haycraft and Smytheman were there as well. Probably over drinks, he agreed to give the four young people 17 shillings, 6 pence for the stolen items, an amount they accepted and promptly divided among themselves "share and share alike." At the same meeting Whiting asked if they had any "wipes," meaning handkerchiefs. "If they had," Eaton later testified, they were to come back to the alehouse on Wednesday and Whiting would "buy them of them, and give them as much as any body would."11

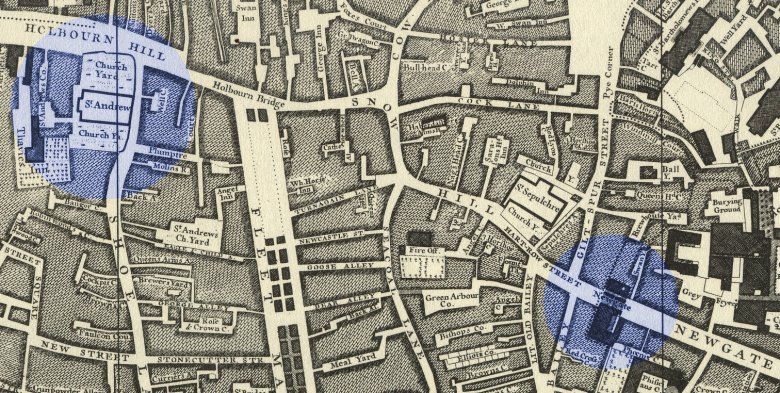

Armed with a search warrant, a parish constable named Thomas Rawlins discovered the stolen goods in Whiting's shop window in Holborn. After Ann Griffiths identified the items stolen from her shop, Whiting and the four robbers were apprehended and taken to Newgate Prison,12 located on the site of today's Central Criminal Court Building, which is popularly known as the "Old Bailey." (See photo below.) Ironically, the place of their incarceration was probably only a short distance from the tavern where they met Whiting--and also not very far from the church where James was christened in 1719! (See map below.)

This map, made only five years after James Haycraft was "transported," shows both the church where he was christened in 1719 and the prison where he was incarcerated in 1744. Although the "ale-house" where he and his cohorts met Whiting is not mentioned by name in the court record, I cannot help but wonder if it was the Swan Inn, shown in the top left of this map, just above Holbourn Bridge.

Of the British capital's fourteen prisons, Newgate was "the most ancient and notorious," known to Londoners "as 'hell above ground.'" Prisoners awaiting trial had "heavy iron manacles…clapped on their hands and feet" and were thrust into the "hold," a dark room with a stone floor, which "was entered by a hatch measuring fifteen by twenty feet." Inside was a single "barrack bed" on which a prisoner could sleep if they could stand the smell. Disorderly prisoners were chained to ring bolts placed around the room, from which they would be released provided they were willing and able to pay a fee to the jailor or "turnkey." Removal of the manacles also required payment of a fee.13

The "Old Bailey," seen here in a 2009 photo taken by the author, stands on the site of Newgate Prison.

Fortunately for the four young burglars, justice was reasonably swift. On 12 April 1744 they were questioned by Justice Poulson, to who they each confessed their role in the crime (although at first Haycraft claimed that he and Smytheman had found the items in a trunk while on their way home from an early morning sweeping job). At their subsequent trial, which was held on 10 May 1744, William and Ann Griffiths, Thomas Rawlins, and Francis Whiting testified against them. Although some of their own statements at the trial were contradictory, there seems no doubt that all four young people were guilty as charged and not surprisingly, Haycraft and Smytheman were so found, as was Eaton. Whiting was bound over for trial at the next session, "for receiving those goods knowing them to be stolen."14 Surprisingly, Ann Henley was acquitted. However, she was not immediately released but "kept in custody to be evidence against" Whiting at his trial, at which he was also acquitted on 28 July that same year after several character witnesses attested to his honesty.15 What became of Henley afterwards is a mystery. There seems to be evidence she ever left England.

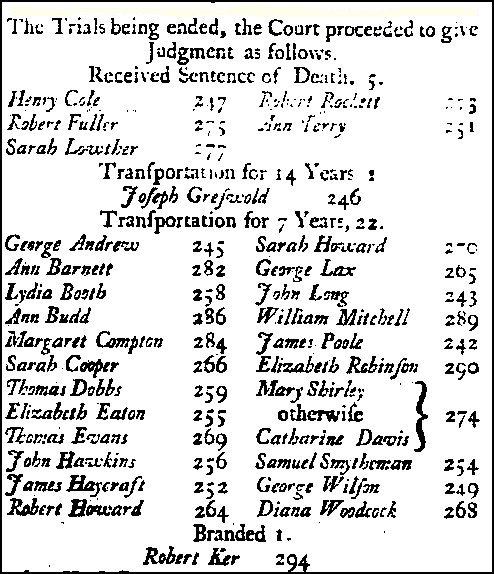

As punishment for their crime, Haycraft, Smytheman, and Eaton, along with several other petty criminals, were sentenced to seven years "transportation" to America. They were fortunate. Five people who stood trial at the same court session were sentenced to death, no doubt by hanging. One, Joseph Griswold or Greswold, was sentenced to fourteen years transportation. Another, Robert Ker, was branded or "burnt in the hand."16

Although criminals had been "transported" to America as early as the mid-seventeenth century, it was not until after the Transportation Act was passed by Parliament in 1718 that "the sentence of seven year's transportation to the American colonies became the standard punishment for crimes other than the most trivial or most heinous." For both Britain and America, transportation was "a multiple blessing." By siphoning off Britain's surplus population, the practice of taking "the worst elements in the country" across the Atlantic to America not only relieved the "pressure on overcrowded...penal institutions" it also decreased "the heavy expense of poor relief." At the same time, it provided colonial planters, particularly in Virginia and Maryland, with "an abundant and unfailing source of free labour to be provided by able-bodied men, and children to whom he [the planter] had no contractual obligations during their term of service." Altogether, it is estimated that "some 50,000 men, women, and children," most of whom "belonged to the poorest class and...were sentenced for crimes which today might incur a small fine...or probation" were transported to America between 1614 and 1775.17

The above summary of the London and Middlesex County court session for 10 May 1744 includes the name of James Haycraft and two of his friends, Samuel Smytheman and Elizabeth Eaton, who were also convicted. The numbers beside each name are simply court case numbers and have no other significance.

In May 1744, probably at Blackfriars Bridge, Haycraft was taken in chains aboard the Justitia, the vessel that would take him and his fellow convicts to America. Altogether, twenty-five people were sentenced to transportation in Middlesex County Court between February and May. Although we cannot be certain, it is probable that all were transported aboard the Justitia. In alphabetical order, the names of the nine women and sixteen men were as follows:

- George Andrews*

- Sarah Ball

- John Bluck*

- Ann Budd*

- Eleanor Callen

- Archibald Campbell*

- George Challener

- Margaret Compton

- Henry Creed

- Elizabeth Eaton*

- Elizabeth Edwards, alias Lareman

- David Flint

- Mary Fowler

- John Gerrard

- James Gregory

- Joseph Griswold or Greswold*

- James Haycraft*

- Julius Hunt

- Johanna Jewers

- John Lloyd

- Thomas Page

- Ann Phillips

- William Robinson

- Samuel Smytheman*

- William Staples

*Indicates this person known to have sailed aboard the Justitia.18

|

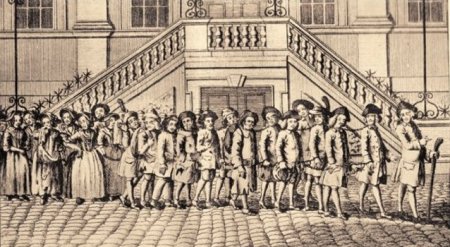

This notice (above), which appeared on page 281 of the May 1744 issue of the London Gentleman's Magazine (volume XIV), names the five persons who received death sentences at the same court session where Haycraft and his friends were tried and sentenced to "transportation." The date however, is wrong; the trial took place on Thursday, 10 May.

|

|

As the Justitia, one of two "flagships" of the convict fleet (the other was the Tryal),19 sailed down the River Thames toward the sea, it seems unlikely that James Haycraft and his fellow transportees, no doubt chained together in a dark, dank hold below decks, were able to take a last look at their English homeland. I cannot help but wonder what James was thinking as the voyage began. Did he think he might return to London some day? (He didn't.) Was Ann Henley, the "wife" the hapless young chimney sweep was forced to leave behind, in his thoughts? Surely, she must have been. And did Ann likewise think of James as she sat in a Newgate Prison cell, knowing that the last time they would probably ever see one another was in the courtroom? Unfortunately, we are left only to imagine.

Although the situation in which he found himself was unfortunate to say the least, James Haycraft probably did not know that it could have been far worse. On 17 April 17 1744, at the same time James and his friends were sitting in Newgate awaiting trial, the previous captain of the Justitia, Barent Bond, was himself brought to trial on four counts of "murder on the high seas." The charge stemmed from a voyage a little more than a year earlier, when 163 convicted felons and indentured servants were brought aboard. The ill treatment they received at the hands of Bond during the voyage to America resulted in no less than forty-five deaths. Remarkably, despite a preponderance of evidence against him, the sadistic captain was acquitted but he "never again" worked "in the transportation trade, at least in England." Afterward, Bond went to America, where he died in Maryland a few years later.20

This is what the Thames estuary looked like in the mid-eighteenth century, when James Haycraft was taken from here as a convict to America.

Jack Campbell, about whom nothing is known, was Bond's replacement as captain of the Justitia when the vessel crossed the Atlantic in the spring of 1744.21 Whether he treated his unwilling passengers any better or any worse that his predecessor I am unable to say. In either event, we know that James Haycraft and Samuel Smytheman survived the voyage, which lasted from six to eight weeks, because they both have descendants living in the United States today. (What became of Elizabeth Eaton is unknown.) Although official records only name "America" as its destination, at the end of the voyage the Justitia probably anchored in Chesapeake Bay, off the Virginia shore. There, at same unnamed port, Campbell set about ridding himself of his unfortunate passengers "selling" them at auction to the highest bidder, undoubtedly to be used in most cases as laborers on tobacco plantations until the expiration of the term of their sentence. The way this was accomplished was described in the Old Bailey Sessions Papers, as follows:

They are placed together in a Row, like so many oxen or cows, and the Planters come and survey them; and if they like 'em, they agree for price with the person entrusted with the selling of 'em. And after they have paid the money, they ask 'em if they like him for Master and is willing to go with him. If they answer in the Affirmative, they are delivered to him as his Property. If, on the contrary, as sometimes happens, they should answer in the Negative, the Planter has his money again and another Planter may make choice of him, whom he may likewise refuse, but no more, for with the Third it seems, he is obliged to go, whether he likes him or not. As there are frequently People who run away from their Masters, there is a reward of twenty shillings paid for the taking of 'em, which makes it very difficult for 'em to escape. When a Master gives them a discharge, he always gives them a Pass, by the Authority of which they may safely go anywhere; and without one, they are liable to be put into a Gaol and confin'd for some days to see if any Enquiry be made after them.22

One felon, sentenced in 1738, later described the process in a book he wrote about his experiences:

The Captain ordered a Gun to be fired as a Signal for the Planters to come down, and then went ashore; he soon after sent on board a Hogshead of Rum and order'd all the Men Convicts to be close shaved against the next Morning, and the Women to have their best Head Dresses put on, which occasion'd no little Hurry on board, for between the Trimming of Beards and the putting on of Caps, all hands were fully employed. In the morning the Captain ordered publick Notice to be given of a Day of Sale; the Convicts, who were pretty near a Hundred, were all ordered upon Deck, where a large Bowl of Punch was made, and the Planters flock'd on board.23

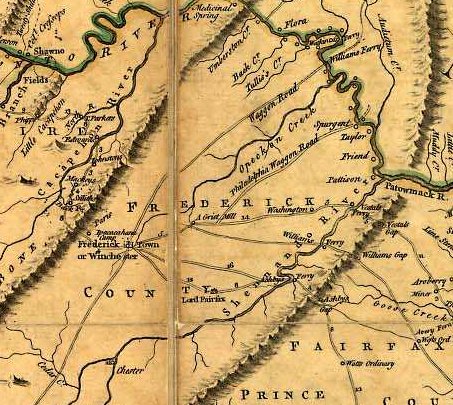

Some researchers believe that James Haycraft was indentured first to George Neville, a planter who in 1743 obtained 181 acres of land "beginning on the west side of the Bull Run Mountain on the drains of Broad Run" in Prince William County. "Neville's Ordinary," a colonial inn reportedly owned by Neville and visited on at least one occasion by George Washington (during the time he worked as a surveyor), is clearly shown on a 1751 map of Virginia drawn by Joshua Fry and Peter Jefferson (not Thomas Jefferson as some sources mistakenly report) and printed by Thomas Jeffreys, "Geographer to his Royal Highness the Prince of Wales."24 In 1759 George Neville's land became part of newly formed Fauquier County. Later, Haycraft's "master" reportedly became George's son, John, who after reaching adulthood and getting married, moved west to neighboring Frederick County (see map below), where for a time he served as sheriff.25

It appears that James Haycraft was himself married either just before or just after his indenture expired in 1751, at which time he was about thirty-two years of age. Together, he and his unknown wife in America had four children--one daughter who died in infancy and three sons: James, Samuel, and Joshua.26 Our only evidence of his presence in Frederick County is the will of a man named James Taylor, which James Haycraft witnessed on 18 October 1760.27 After James and his wife died about 1762, John Neville took the three boys into his household and cared for them until they reached their majority.28

Unfortunately, there are no known records proving that James Haycraft was indentured to either George or John Neville. This alleged connection is only conjecture based on the fact of John Neville's becoming guardian of the Haycraft brothers following their parents' deaths and also the fact that John Neville was only thirteen-years-old (born 26 July 1731) when James Haycraft arrived in America in 1744, which therefore suggests that his father was the one to whom James was originally indentured.

Some researchers (including me) have wondered if the reason that John Neville became the Haycraft brothers' guardian was not because he was James Haycraft's master but because he was the boys' uncle by marriage. In short, it has been speculated that James Haycraft's wife was none other than John Neville's sister. Unfortunately, there is little likelihood of that owing to the fact that John Neville had six brothers and only one sister, Ann, who reportedly married a fellow named William O'Bannon.

There is also the matter of whether or not John Neville was actually George Neville's son. No fewer than three published biographies state this quite clearly, with no ambiguity whatsoever.29 Another source identifies him as the son of a Richard Neville.30 However, one researcher-William Scroggins of Taylor Mill, Kentucky, correctly pointed out in 1989 that George Neville's will (dated 26 February 1774 in Fauquier County, Virginia) does not name John Neville (who lived until 1808) or any other surviving son as an heir. Based on his research, which appears to have been quite thorough, Scroggins holds that John Neville was the son of George Neville's youngest brother, Joseph Neville, who was also a Prince William County planter, who was born in 1707 and died in 1790.31 Many present-day researchers appear to have accepted Scroggins findings and I am inclined to do so myself. Thus the question arises: Does this mean that James Haycraft was instead indentured to Joseph Neville? Again, the answer is we cannot know for sure since there is no known documentation regarding Haycraft's indenture, although of course it is not outside the realm of possibility that Joseph was his "master."

Whatever his reasons might have been for taking the Haycraft brothers into his home, the three boys almost certainly could not have been more fortunate. From all accounts, Neville was an educated man "of very frank and hearty address, of sound judgement, of much firmness and decision of character" as well as "of plain, blunt manners, [and] a pleasant companion." It was said too that was a great storyteller, able to "give interest" even "to trifling incidents." Several biographers have called attention to his "early acquaintance of Washington, both of whom were about the same age," which apparently led him to join the future president in General Braddock's ill-fated expedition against the French in 1755. John Neville's son Presley, with whom the Haycraft brothers grew up, is reported to have also been an "accomplished gentleman."32

NOTES

1Samuel Haycraft, Jr.. Haycraft's History of Elizabethtown, Kentucky (Hardin County Historical Society, 1960), 120.

2J. M. Armstrong, Biographical Encyclopedia of Kentucky of the Dead and Living Men of the Nineteenth Century (Cincinnati, Ohio: 1878), 222.

3 St. Andrew's Holborn, Holborn Circus, City of London, Parish Register: Christenings, 1719: Guildhall Manuscripts Archive, London Metropolitan Archives, City of London, 40 Northampton Road, London EC1R 0HB, England, United Kingdom.

4Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org), version 6.0, 10 March 2012), May 1744, trial of James Haycraft Ann Henley , otherwise Haycraft, Samuel Smytheman, Elizabeth Eaton (t17440510-9). See also: Old Bailey Sessions Papers, 10 May 1744, 116-7 & 144, Guildhall Library Manuscripts Section, London Metropolitan Archives, City of London, 40 Northampton Road, London EC1R 0HB, England, United Kingdom; and Middlesex Sessions Rolls--Indictments 8th to 10th May 1744 (MJ/SR/2819), Folio 9; Middlesex Sessions Roll--Gaol Delivery (MJ/SR/2819), "A perfect calendar of all the prisoners committed to His Majesty's gaol Newgate from the 4th day of April 1744 to the 10th day of May, 1744"; Middlesex Sessions Gaol Delivery Book--September 1736 to December 1745 (MJ/GBB/317), 150, London Metropolitan Archives, City of London, 40 Northampton Road, London EC1R 0HB, England, United Kingdom. NOTE: All subsequent references to this source material shall read "Old Bailey, see note 4."

5 Ibid.; The A to Z of Georgian London (London: London Topographical Society, 1982), 21; Old Bailey, see note 4.

6Old Bailey, see note 4.

7Benita Cullingford, British Chimney Sweeps: Five Centuries of Chimney Sweeping (Chicago: New Amsterdam Books, 2000), 23-7, 34-8 & 50.

8Old Bailey, see note 4.

9Old Bailey, see note 4.

10Old Bailey, see note 4.

11Old Bailey, see note 4.

12Old Bailey, see note 4.

13Peter Coldham, Emigrants in Chains (Baltimore, Maryland: Genealogical Publishing Company, 1992), 20.

14Old Bailey, see note 4.

15Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 6.0, 10 March 2012), July 1744, trial of Francis Whiting (t17440728-30).

16Old Bailey, see note 4.

17Coldham, Emigrants in Chains, 3, 7 & 43.

18Peter Coldham, Bonded Passengers to America, vol. II, Middlesex, 1617-1775 (Baltimore, Maryland: Genealogical Publishing Company, 1983), 7, 14, 27, 39, 45, 51, 60, 67, 86, 96, 99, 106, 113, 126 (James Haycraft listed this page), 140, 147, 169, 203, 210, 229, 248, 252 & 329.

19Coldham, Emigrants in Chains, 104.

20Ibid., 108-10.

21Ibid., 174

22Ibid., 120-1.

23Robert Goady, The Surprising Adventures of Bampfylde Moore Carew, King of the Beggars (London: W. Salter, 1812) 84.

241751 map of Virginia drawn by Joshua Fry and Peter Jefferson and printed by Thomas Jeffreys, "Geographer to his Royal Highness the Prince of Wales," map collection, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

25Edward Purcell, Who Was Who in the American Revolution (New York: Facts on File, Inc., 1993), 348.

26Haycraft, 120-1.

27J. Estelle Stewart, Abstracts of Wills, Inventories, and Administration Accounts of Frederick County, Virginia, 1743-1800 (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company, 1980), 128.

28Haycraft, 121. 0

29John W. Jordan, Colonial and Revolutionary Families of Pennsylvania (Baltimore, Maryland: Genealogical Publishing Company, 1978), 1163; J.M. Toner, Ed., Journal of my Journey Over the Mountains, by George Washington (Albany, New York: Joel Munsell's Sons, Publishers, 1892), 20; History of Pittsburgh and Environs (New York and Chicago: The American Historical Society, 1922), 117.

30 Jordan, 887.

31John Neville family tree <>http://wgscroggins.kueber.us/Neville1_John_born_1662.pdf> [Accessed 10 March 2012].

32Neville B. Craig, The History of Pittsburgh: With a Brief Notice of Its Facilities...(Pittsburgh: Pennsylvania: John H. Mellor, 1851), 124 & 230-1.

|