Return to Richland College 1972

|

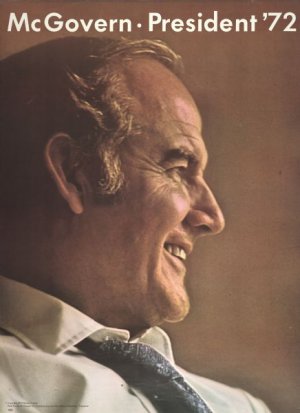

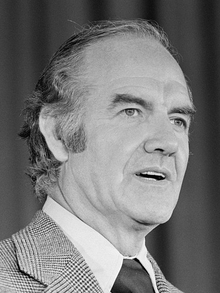

Remembering the 1972 McGovern Rally in Dallas, Texas By Steven R. Butler, Ph.D. Author's note: This is a slightly revised version of an article that first appeared in the Richland [College] Chronicle, Feb. 3, 2009. In 1972 I was twenty-three years old, married only two years, and recently released from active duty in the Navy. I was also one of the first 3,500 students enrolled at the brand new Richland College in Dallas, Texas. That year Senator George McGovern of South Dakota was the Democrats' presidential candidate. Like Barack Obama some thirty-six years later, McGovern was very popular among college students, largely because of his stand against the war in Vietnam. Four years earlier, Nixon had won the presidency on the basis of having a secret plan to end the war. When Richland first opened its doors four years later, the end of the war was still not in sight and I was not only disappointed but also angry that he had not fulfilled his pledge. I occasionally joked to my classmates that Nixon's plan was so secret that even he did know what it was. Like many young people, I became a McGovern supporter. Nearly everything I read or heard about him appealed to me. What struck me was that unlike Nixon, Senator McGovern seemed to possess a genuine concern for ordinary Americans who were struggling, like my young wife and I, to make ends meet. Several of my generation's most popular musicians and entertainers also supported McGovern, people like James Taylor, Joni Mitchell, Paul Simon, and Barbra Streisand.

In his book The Making of the President 1972, author Theodore H. White described the Dallas rally as "first class" but also remarked that in what was then Texas' second largest city, "liberal Democrats [were] still an underground, suppressed by the dominant ethic of the money men and the tyranny of the proprietary press, as hostile to McGovern as the liberal press was to Nixon." For example, he added, "The Dallas Morning News…announced McGovern's arrival and rally on its eighth page, the front page being dominated by a hotdog-eating contest." Even so, White observed, "McGovern loyalists turned out a night crowd of 3,000 enthusiasts, waving their blue banners, signs held high: 'MAKE AMERICA HAPPEN AGAIN, MC GOVERN.' 'MC GOVERN-WE LOVE YOU.' 'COME HOME AMERICA-MC GOVERN.' 'FOUR MORE YEARS-NO THANKS.'" Former Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall introduced McGovern, who although tired, reported White, "was buoyed by the crowd. No longer the Gentle George of his television commercials but George the Wrathful, he struck out on the week's pre-planned theme, the inequity of the tax structure: 'A businessman can deduct the price of his $20 martini lunch and you can help pay for it, but a workingman can't even deduct the price of his bologna sandwich.'"

Following McGovern's remarks, which lasted about half-an-hour, campaign workers mixed with the crowd, soliciting donations of one or two dollars, which was just about the most I could spare at the time. McGovern himself also worked his way through the audience, greeting supporters and shaking hands. Unfortunately, when he reached the spot where my wife and I were standing, I was holding my infant son in my arms and had to forego shaking hands with the man I admired so much for fear of dropping my child! I later regretted that my wife and I had not tried to find a babysitter that night and also that I had not brought a camera or tape recorder to make a record of the rally. Nor did I write about the event for the Richland Mandala (the forerunner of the Chronicle), even though I was on the college newspaper staff, for the simple reason that the rally occurred several weeks before our first issue came out and by then it was old news. On Tuesday, November 7, 1972 I voted for the first time ever in a presidential election, in the gymnasium of Vivian Field Junior High School in Farmers Branch, where I had been a student when John F. Kennedy was president. Then I went home and that night, my wife and I watched the election returns on TV until our hopes were crushed by the news that Richard M. Nixon had not only won another term as president but also that he had defeated Senator McGovern in the biggest electoral landslide in U.S. history, winning forty-nine out of fifty states. In Texas, mine was one of the 1,154,289 votes that had gone to McGovern. But 2,298,896, or 67 percent, had voted for Nixon. I felt even more let down when I learned that the anticipated "youth vote," which the twenty-sixth amendment had made possible by lowering the voting age to eighteen in 1971 (a bloc the McGovern campaign was counting on), "failed to materialize," as Theodore White points out in his book. As it turned out, about 52 percent of voters aged 18 to 24 had cast a ballot (as compared to roughly 68 percent of older voters), which was actually a higher percentage than in all subsequent presidential elections except the most recent (2008). The trouble for McGovern was that of those youth who did vote, support for him was only slightly higher (also about 52%) than for Nixon. This statistic reveals that not all "Baby Boomers" were as politically liberal as the popular media seemed to imply. The fact that 48% did not vote at all suggests that far too many young people either had no interest in politics or were too disillusioned by then-recent events to think their vote might make any difference. Copyright © 2008-2022 by Steven R. Butler. All rights reserved. |

White was right on target when he later wrote "The crowd loved every word, cheering and rocking with excitement, at one with McGovern." But there was a problem in Texas, he also noticed, which "was [the need] to 'de-radicalize' George McGovern's image." The Dallas crowd, he correctly observed, "was the same kind of crowd George McGovern's volunteers had assembled for the primaries--young people, blond, handsome, loose-limbed in loose clothing, with the look, many of them, of students. They wanted the radical, crusading George McGovern [and] he was giving the audience what it wanted." However, he remarked further, "there were no blacks in this group, and there were few Latin Americans." Perhaps most telling of all, White pointed out, was the absence of prominent Democrats like Robert S. Strauss, "the Democratic Committee's former National Treasurer, soon to be its new National Chairman," and "Dolph Briscoe, the Democratic nominee for Governor."

White was right on target when he later wrote "The crowd loved every word, cheering and rocking with excitement, at one with McGovern." But there was a problem in Texas, he also noticed, which "was [the need] to 'de-radicalize' George McGovern's image." The Dallas crowd, he correctly observed, "was the same kind of crowd George McGovern's volunteers had assembled for the primaries--young people, blond, handsome, loose-limbed in loose clothing, with the look, many of them, of students. They wanted the radical, crusading George McGovern [and] he was giving the audience what it wanted." However, he remarked further, "there were no blacks in this group, and there were few Latin Americans." Perhaps most telling of all, White pointed out, was the absence of prominent Democrats like Robert S. Strauss, "the Democratic Committee's former National Treasurer, soon to be its new National Chairman," and "Dolph Briscoe, the Democratic nominee for Governor."