|

The Ward Family

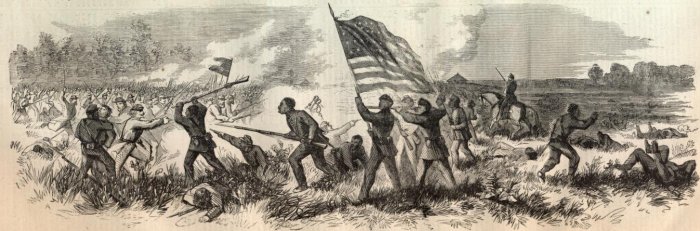

Ward Family MORRIS WARD, JR. The two biggest mysteries surrounding the life of Morris Ward, Jr. are his birth and his death. According to some census records, he was born in Florida in June 1846, yet in 1840 and 1850 his birth family was resident in Alabama. So how did he come to be born in Florida (if true)? Presently, no one knows. All we can be sure of is that he was the sixth son and seventh child of Morris Ward, Sr. and his wife, Elizabeth Ann (Wilson) Ward. Morris Jr. spent his early childhood in Pike County, Alabama. In 1857 or 1858, his family removed to Texas, where the federal census taker recorded in 1860 that not only were they residents of Upshur County, but also that young Ward was already being called "Doc"-a nickname he would apparently keep for life although the reason for it has been lost to history. Morris "Doc" Ward in the Civil War In February 1861, despite the outspoken opposition of Governor Sam Houston (who was forced out of office when he refused to take an oath of allegiance to the Confederacy), Texas seceded from the United States and joined the newly formed Confederate States of America. On April 15, 1861, the Civil War officially began when President Lincoln declared the southern states in rebellion after South Carolina troops fired on Fort Sumter in Charleston harbor. A little more than a year later and only a month or so short of his sixteenth birthday, Morris Ward Jr. enlisted as a private in Company D, 28th Texas Cavalry (Dismounted). The date was May 9, 1862. His term of service was three years or the duration of the war. Like three-fourths of all white Southerners, "Doc" Ward" did not come from a slave-holding family. According to the 1860 federal census his father, a simple farmer, owned only $150 worth of personal property. (The value of his real estate was left unrecorded.) Although it is an indisputable fact that the southern states were led into secession by a relatively small group of powerful slaveholding politicians in order to protect and perpetuate the institution of African slavery, it is doubtful that "Doc" Ward gave much thought to such matters. At fifteen, an age at which few individuals are capable of critical thinking, he was almost certainly told, and believed, that by joining up he would simply be defending "his country" against Northern invaders who wanted to destroy Southern "rights"-which at that time included the dubious right to hold human beings in bondage against their will. Because young Ward left no journal or letters that we know of, recounting his personal experiences of the war are unknowable to us, but the movements of his regiment and the battles in which they participated have been well documented. The colonel of the 28th Texas Cavalry was Horace Randal, a West Point graduate and former U.S. army officer. When the Civil War began, Randal resigned his U.S. Army commission. Almost immediately the Confederate government offered him a commission as a second lieutenant, but he refused it. Instead, he fought as a private soldier in Virginia before returning to Texas. In 1862, he became an officer once again. During the summer of 1862, after Randal took over as colonel of the 28th Texas Cavalry, the regiment became part of the 2nd Brigade of General John G. Walker's Texas Division. It had previously been brigaded under General Ben McCulloch of Texas Ranger fame. This division was the largest unit of Texans in the war. These troops, by their frequent long marches over the too-often muddy roads of Arkansas and Louisiana, earned the nickname "Walker's Greyhounds." The first battle in which the 28th Texas Cavalry participated was at Milliken's Bend (June 7, 1863) during the Vicksburg campaign (spring and summer 1863). They later participated in the Battle of Mansfield (April 8, 1864), and the Battle of Pleasant Hill (April 9, 1864) during which Colonel Randal was fatally wounded. In the spring of 1863, Walker's Division (including the 28th Texas Cavalry) was at Camp Wright, located four miles north of Pine Bluff, Arkansas. There, on April 23rd, the division received a message from General Theophilus H. Holmes to General Walker, ordering the latter to proceed "without delay" to Monroe, Louisiana via Camden, Arkansas, was read to each regiment. The reason for the order? The Confederates had reason to believe the Federals would soon be making an attempt to take western Louisiana. In his order, General Holmes passed on the sentiments of General E. Kirby Smith, commanding general of the district, who expressed "confidence in (the division's) strength, patriotism, and valor...Better officers and men no division can boast of. The Confederacy may well be satisfied with security of its interests entrusted to them." The following day, Walker's division marched out of Camp Wright and headed south on the road leading through Pine Bluff. Recent heavy rains having recently flooded the Saline River and Moro Creek, they did not go to Camden (from which they would have gone by boat down the Ouachita River to Monroe) but instead marched straight south for Louisiana. Their route would take them through Monticello, the villages of Lacy and Fountain Hill, and thence to Hamburg, Arkansas. Along the way, an officer of the 17th Texas Infantry, Captain Elijah P. Petty, sent letters home to his family in Bastrop, Texas. Well-written and informative, these letters traced the route of Walker's division and told of its experiences along the way. By April 29, the division had reached Fountain Hill. There, wrote Captain Petty, "We have just received orders to remain at this place until further orders. These...may come at any moment." Describing the soldiers' progress through southern Arkansas Captain Petty continued, "Through Drew County we had an ovation nearly the whole way. The ladies in perfect swarms were on the roadside at every house. At points the whole neighborhood would assemble and such waving of handkerchiefs and throwing boquets (sic) I havent (sic) seen hardly in my life." "At Monticello," he wrote, "there were more ladies and prettier ones than I ever saw in my life. Every house and every corner and every yard swarmed. At the Court house there was a perfect crowd of them. Such a fluttering of handkerchiefs, such a showering of flowers and boquets (sic), such a rushing of negroes and little boys bearing flowers and boquets (sic) to the ranks as then and there took place did the hearts of the weary soldier good and in return hats waved and cheer after cheer went up such as Monticello and this portion of the Confederacy ever witnessed before." In contrast to his happy report of the welcome the Confederate soldiers received along their line of march, Captain Petty complained of Federal troops in the vicinity of the Mississippi who "having failed to take Vicksburg and Port Hudson have become mad and now going out into the country bordering that stream and are destroying everything particularly crops, provisions and farming utensils; burning residences, gins, etc.; stealing negroes and every thing they can lay their infernal hands on." No doubt Captain Petty echoed the sentiments of many of those in Walker's division when he declared he hoped the "Black Flag" (signifying "no quarter") would be raised and he would "get to fight under it." On May 1, 1863, the division was camped three miles west of Hamburg, Arkansas "on the road leading to a little place called Mary Saline." In Hamburg the night before, the local citizens had given a dance for the soldiers' benefit. Reported Captain Petty, "it was a grab game. Men pitched in without ceremony or introduction and actually pulled the women out on the floor to all of which they did not object and cheerfully submitted." Upon reaching Ouachita City, the troops took boats down the Ouachita City to Trenton, a small village about two miles north of Monroe-a distance of about fifty miles, which they traveled in just three hours. There, near Trenton, they set up camp. From this camp, two miles west of the town on the Shreveport road, Captain Petty wrote to his wife, remarking, "The Washita Valley is a magnificent farming section. There is immense wealth in it but the people are alarmed & this road is lined with negroes, wagons & families en route to Texas. They came from the Mississippi River and all the Bayous bordering on it. I never saw such an exodus before." In this same letter, Captain Petty wrote of his concern was for his fellow Texans: "Texas will be over run I fear with negroes. Its immense capacities will be taxed too heavily and her own citizens will have to suffer for food." On Saturday, May 9, 1863, Walker's division filled fourteen steamboats, which set out for Alexandria, Louisiana by way of the Washita River, Little River and Catahoula Lake. Wrote Captain Petty: "it presented a grand scene to see us steaming, one after another down this beautiful river with banners fluttering, bands playing, men huzzaing and cheering, with the bank lined with ladies with palpitating hearts and fluttering handkerchiefs." However, this fleet of steamboats had gone only seventy miles downriver when General Walker, on the lead boat, ordered them to turn about and return to Trenton. When no reason was given for the order, quite a bit of excitement and curiosity was generated. Later, it was learned a courier had given General Walker news that the Federals had taken Alexandria. To proceed further would have put the whole division in danger. The boats arrived back at Trenton about 2 o'clock in the morning on Sunday. The division remained encamped near Trenton until May 15, when it left on a forced march to reinforce General Richard Taylor's troops near Natchitoches. By May 19 Walker's men were four miles northeast of Sparta, in Bienville Parish. The next day they marched nineteen or twenty miles to a point near Black Lake in Natchitoches Parish. Two days later they reached a point about a mile from Campti, a town on the Red River. There, wrote Captain Petty, they "encamped in a beautiful grove on a considerable lake the water of which is not very good...and is filled with alligators." From Campti, Walker's Division traveled by steamboat, down the Red River to Alexandria-which had recently been vacated by the Federal troops. They no sooner arrived, on the 26th, than they were told to turn around and return to northeastern Louisiana. The Federals, it was believed, were closing in on Vicksburg, Mississippi. "Vicksburg is in a critical condition, but I have every confidence in the skill of our generals and in the heroism and bravery of our men" wrote Captain Petty. From Alexandria, the soldiers moved on to the Little River where they boarded boats at La Croix's Landing. Traveling down the river they passed through Catahoula Lake, back into the Little River, then into the Black River at Trinity-where the Ouachita, Tensas and Little Rivers come together. They then traveled north up the Tensas River "steaming like life in the direction of Vicksburg." By May 30th, they were camped on the Tensas, "about 9 or 10 miles west of the Mississippi River and about 20 miles below Vicksburg." Shortly upon arrival a scouting party was sent out which captured a Federal soldier "and several negroes with a cart & some tricks & provisions." On May 31, McCulloch's brigade came under fire by Federal artillery and one man was killed. Randal's troops were six miles away during the fight and so did not come under fire that day.Milliken's Bend was a Federal camp lying immediately above the town of the same name, nearly opposite Vicksburg-on the Louisiana side of the Mississippi River. The camp was 150 yards wide and was sheltered by two levees, one on the landside and the other on the Mississippi. The 23rd Iowa Infantry and four regiments of ex-slaves from Louisiana and Mississippi known as the African Brigade garrisoned it. In all, the garrison, commanded by Colonel Hermann Lieb, consisted of 1,061 men. Early in the morning of June 7, while Randal's brigade waited in reserve, Confederate scouts for McCulloch's Brigade approached Milliken's Bend. About a mile and a half from the Federal camp the Federals fired them on. Fleeing, the scouts were shot by McCulloch's men who initially mistook them for the enemy charging. McCulloch pressed forward and formed up three regiments--Allen's, Fitzhugh's and Flournoy's-at the landside levee. They then charged over the levee, ten feet high and topped with cotton bales, crying "No Quarter!" Many of the African-American soldiers fought back the hardest, after some of their number, along with the white soldiers had retreated. The Confederates engaged them in hand-to-hand combat with bayonets and muskets used as clubs. Other black soldiers, found hiding in the fortifications, were killed, rather than taken prisoner.

As the battle progressed, the Confederates drove the Federals into an open area between the two levees and toward the riverbank. However, and unfortunately for the Southern soldiers, the Federal gunboat Choctaw opened fire with heavy artillery. As a result, McCulloch's men were forced to fall back to the landside levee. General McCulloch then sent for reinforcements. A Confederate gunboat, the Lexington, arrived about 9 o'clock in the morning and lobbed some shells into the woods. About noon, General Walker arrived with Randal's brigade, but the men were exhausted from lack of water and the heat of the day. The battle was not resumed. In the evening General Walker withdrew both McCulloch's and Randal's men toward Richmond, Louisiana. Randal's troops later boarded a train at Delhi-to be taken back to Monroe, for further transportation back to the Red River. Upon arrival they embarked aboard boats for the trip down the Ouachita River to Columbus, but there, instead of going on to Alexandria as they expected, they were turned back toward Richmond. By the time they rejoined the rest of Walker's division they were nearly worn out from all the traveling they had done. J. P. Blessington, in Walker's Texas Division, wrote:

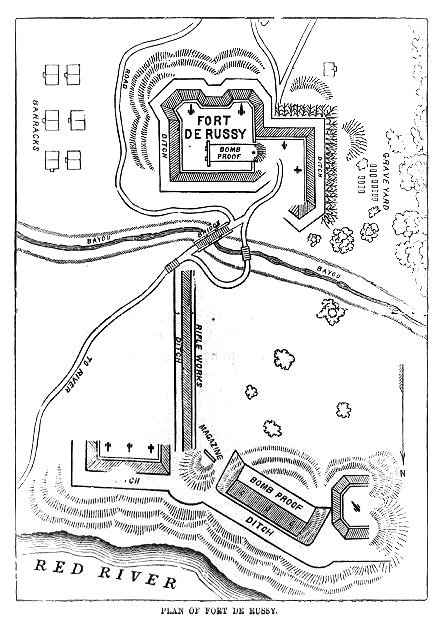

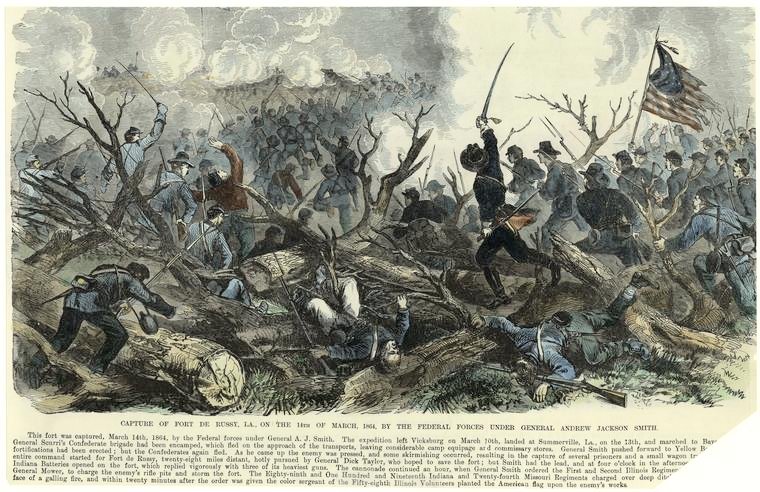

At Mounds Plantation on June 29, Randal's brigade and Parson's Texas Cavalry surrounded a Federal fort built atop an ancient Indian mound. Black soldiers whose three white officers asked to surrender and be taken as prisoners of war while their troops, numbering 113 men, were to be surrendered unconditionally garrisoned it. The Confederates agreed to these terms. General Walker, upon hearing of it, probably echoed the sentiments of many a Southern soldier when he remarked, "I consider it an unfortunate circumstance that any armed negroes were captured." To the Southern way of thinking, it was the foulest of deeds for ex-slaves to be pitted against their former masters. Unable to come to the relief of Vicksburg, which by now was under heavy siege by Federal troops under General Ulysses S. Grant, Walker's men remained camped near Delhi, from where they could hear the enemy cannonade. After waiting anxiously for word, to their dismay news came on July 7 that Vicksburg had been taken three days earlier. Some of the men felt that with the fall of this important Confederate city, the war was as much as over. The same day that news came of the fall of Vicksburg, Walker's division marched up Macon Bayou to Monticello, returning the next day. Three days later they boarded a train for the 40-mile ride to Monroe. Next, on July 19, they were ordered to go to Alexandria via Campti, on the Red River. Part of the journey was made by water. At Alexandria, they encamped until August 10, moving on to Camp Green-located in the woods some 20 miles southwest of Alexandria, where they remained until August 31. On September 1 Randal's Brigade marched to Harrisonburg, Louisiana, where the men of the 28th Texas participated in an unsuccessful attempt to prevent Union troops from destroying Fort Beauregard, a "small, twelve-gun post situated on a hill" beside the Ouachita River. They also lost two of their men, who were captured by the Federals and held as prisoners, apparently for the duration of the war. Afterward, the brigade returned to the vicinity of Alexandria. On October 3, 1863, Union forces in Louisiana made the first step toward a planned invasion of Texas by occupying New Iberia. During much of that month, Walker's division-called "Walker's Greyhounds" by Federal forces on account of their seeming ability to cover vast distances in a short amount of time-was kept busy by a series of confusing marches. In November 1863, following the execution of a would-be deserter, the men of the 28th Texas Cavalry (Dismounted), along with the rest of Walker's division, "marched to the Mississippi River to prey on enemy transports." During that time there was also "an abortive movement to capture Plaquemine." Following Walker's expedition to the Mississippi, young Morris Ward, Jr. and his companions in the 28th Texas Cavalry (Dismounted) spent the winter of 1863-1864 (December 1863 through February 1864) in winter quarters near Marksville, Louisiana. Camped in a thick forest, they chopped down trees and built log huts for shelter. During these months, some men were allowed to go home to East Texas on furlough, but we do not know if the now seventeen-year-old Ward was among them. Most of the men were kept busy drilling on a nearby prairie and helping to fortify Fort DeRussy, the so-called "Gibraltar of the South" that was located near the point where the Red River joined the Mississippi. On March 4 and 5, 1864 there was a mutiny in which "approximately half of the 28th (primarily Companies A, F, H, I, and K) refused to do duty." We do not know if Morris Ward took part in the mutiny but because he was assigned to Company D, it seems unlikely. In any case, although the ringleaders were arrested, none of the discontented men, most of whom repented and all of whom were needed for the upcoming Red River campaign, were ever punished. The entire regiment, however, was "moved away from other troops to a point near Pearl Lake, about seven miles southwest of Marksville." "From March to the end of April 1864," writes author M. Jane Johansson, "the 28th Texas Cavalry (dismounted) saw its only heavy combat actions of the war." As it turned out, young Morris Ward, Jr. would only be involved in one of these, which may be why he survived the war when many others did not. To capture Shreveport and then invade Texas from the east, Union troops began moving up the Mississippi River in March 1864. To counter this offensive, Walker's division went into action, leaving their camps near Marksville and moving to the vicinity of Cheneyville. Of course, these troops included the 28th Texas Cavalry (Dismounted). Around this time, "Thirty-four men of Company D, commanded by Capt. A.L. Adams...were stationed in Fort DeRussy." One of the thirty-four was Pvt. Morris Ward, Jr., who along with his comrades was stationed at the fort's water battery beside the Red River, located about 700 yards east of the main fortification. On March 14, 1864, after being pounded by artillery from Union gunboats in the Red River and attacked on the landside by Union troops, the 350-man garrison of the supposedly impregnable Fort DeRussy quickly surrendered. Although several men managed to escape into the woods and rejoin their regiment, young Morris Ward was among the twelve men from the 28th who were taken prisoner by the Federals. In a report composed in 1865, a Union General, A. J. Smith, recalled his troops' participation in the attack on Fort DeRussy:

Following the fall of Fort DeRussy, Pvt. Morris Ward and his fellow POWs were taken on gunboats to Baton Rouge, where they were kept in the state penitentiary for three days. On the evening of March 17, they again boarded boats-only this time they were taken to New Orleans, where they arrived on March 18. Because of his captivity, Private Ward missed the battles of Mansfield and Pleasant Hill, Louisiana (April 8 and 9, 1864) and the Battle of Jenkins' Ferry, Arkansas (April 30, 1864), where altogether the 28th Texas Cavalry (Dismounted) suffered their heaviest casualties of the war-38 killed, 95 wounded (many severely), and 2 missing. There is of course no way to know if Ward would have been among the dead or wounded had he been there, but it seems a fair bet to conclude that apart from the danger of illness, he was almost certainly safer as a P.O.W. in New Orleans. During Morris Ward's nearly four-month-long captivity, it is a near certainty that he was incarcerated at the New Orleans Parish Prison, a three-story-tall stone structure built in 1834 and bounded by Orleans, St. Ann, Treme, and Marais streets-near where the Mahalia Jackson Auditorium and Louis Armstrong Park are situated today. The prison was demolished in 1894 and replaced with a more modern structure, which has also since been torn down.

Federal war records state that Ward rejoined his regiment on July 22, 1864 at "Red River, Louisiana" when Union and Confederate prisoners were exchanged. Of course, there is no way to know his state of mind, but we may suppose he was both relieved and at the same time a little upset that he had missed the chance to experience combat. No doubt he and his fellow P.O.W.s were the butt of much good-natured "hurrahing" by the veterans of the battles he had missed. At that time, the 28th Texas was stationed about 20 miles southwest of Alexandria. The following day, they broke camp, marching to Harrisonburg, where the regiment "remained until mid-August." The remainder of Private Ward's service was largely uneventful. Between August 1864 and May 1865, when the regiment finally disbanded, the men spent their time in a variety of camps located in Northern Louisiana and Southern Arkansas, where they drilled, held inspections, and performed mock battles for the entertainment of the local populace. When in the late spring of 1865 it became obvious that the war was lost, many men deserted. Finally, in mid-May, the entire brigade simply disbanded, and everyone went home. Morris "Doc" Ward after the Civil War At the end of the Civil War, Doc Ward was not quite nineteen years old. Most likely he lived at home with his parents in Upshur County until September 16, 1869, when at Starrville in neighboring Smith County, he married Mary Ann Lowry (or Lowrey), daughter of Mark and Elizabeth Lowry. Between 1870 and 1880, Mary Ann Lowry Ward gave birth to five children:

In 1870, when the federal census for Upshur County, Texas was taken, Morris Ward, Jr. and his wife Mary Ann were listed as a farming family with real estate worth $550 and personal property valued at $580. Charles Lowry, Mary's 13-year-old brother, was living with the couple, both of whom were twenty-four-years-old at the time. The following are a summary of land transactions in Upshur County, Texas involving Morris Ward, Jr.: On April 27, 1870, for the sum of $80, Morris Ward, Jr. sold four acres of land alongside the Sabine River to John W. King, including "the landing of a ferry known as King's Ferry and also the right of way through said Ward's tract of land for a public road leading from said ferry." The deed reveals that this land was part of the property for which Morris Jr.'s father had received a patent in 1862. On December 3, 1873, Morris Ward, Jr. and his wife, Mary A. Ward, sold all 160 acres of Morris Ward, Sr.'s original Texas Land Patent No. 551, to Jim Bailey for $200. Wit: Kennedy Gibson and Amanda King. What's puzzling about this transaction is that the four acres that Ward sold to King earlier was not excluded in the deed. This transaction also raises some questions: First, it appears to have left the Ward family landless, so where did they reside afterward? Second: In 1875 and 1876 county tax rolls show Morris Ward, Jr. still as the owner of this property, with taxes due on it. How could that be if he sold it in 1873? On June 24, 1875, for the sum of $520.18, Morris Ward, Jr. was granted title to "a certain Steam Mill & fixtures made by Lane & Bodley of Cincinnati, Ohio of 25 horse power said mill being situated about eighteen miles South of the Town of Gilmer in said county & about 1 1/4 miles South of Texas & Pacific R Road" from B. F. Vanmeter, G. W. Frances and W. J. Frasher. This instrument appears to be an effort to satisfy a debt these men owed to Morris Ward, because it carried some conditions: If Vanmeter, Frances and Frasher paid Morris Ward the same sum of money ($520.18) within 60 days of June 29, 1875, then the title was void. Otherwise, Ward had "the Right to advertise the said mill & fixtures 15 days at the court house in the Town of Gilmer...& sell the same to the highest bidder for cash, after paying and retaining the said sum of $520.18 and all cost of sale" except that Ward had to pay "the overplus if there be any to the said Frances and Vanmeter." Ward also agreed "that in case the said Frances, Vanmeter & Frasher fails to pay said money they said parties may discharge their said amt. of $520.18 in lumber delivered & loaded in the cars on said Texas & Pacific R Road at the customary cash price there ruling in the marked [sic] at the time of said delivery the lumber to be good merchantable lumber." By which one of these methods this debt was eventually satisfied, however, is unknown. On January 9, 1878, for the sum of $1,000, Morris Ward, Jr. purchased 200 acres of land in Upshur County, formerly part of the John Carson Survey, from A.T. Boger and his wife Mattie. The Carson survey lay immediately north of, and adjoined, the 160-acre tract which Morris's father, Morris Ward, Sr., had purchased in 1860. On February 11, 1879, Morris Ward, Jr. and wife, Mary A. Ward, sold 175 acres plus two 10-acre tracts to J. M. Shamborger, for $1,000. No witnesses. This appears to be the very same property that the Wards purchased from the Bogers only a year earlier. From all appearances, this last transaction left the Wards landless again. Where they resided thereafter is unknown, but on January 16, 1880, Mary Ann Lowrey Ward died, only about six months after the birth of her son and last child, Claude Elliot Ward. Her passing must have occurred in Upshur County because she was allegedly buried at Chilton Cemetery, near Big Sandy, Texas. The absence of her name from the 1880 federal census provides further evidence of her passing. Tax records are also helpful in ascertaining the whereabouts of the Ward family. However, they also raise some questions. For instance, considering that he sold his father's original land patent to Jim Bailey in 1873, it's odd that the 1875 Upshur County, Texas tax roll still shows Morris Ward, Jr. as the owner of it, plus 2 acres of the adjoining Carson survey. That year he is also supposed to have owned two horses or mules valued at $150, two head of cattle worth $10, household or kitchen furniture valued at $100, miscellaneous property worth $45, the total value of his property being $1,305. Consequently, his state taxes were $6.52 and poll tax $1.00, making a total of $7.52. His county taxes were $3.26, plus $1.95 special tax, plus 65 cents road and bridge tax, plus 50 cents poll tax, for a total of $6.36. The 1876 Upshur County, Texas tax roll continues to show Morris Ward, Jr. as the owner of his father's original 160-acre patent (but this time with no additional acreage), with one horse or mule worth $75, four cattle worth $20 total, 15 goats or hogs worth $25, household and kitchen furniture worth $30, miscellaneous property worth $30, with taxes due of $7.90 state tax and $6.71 county taxes. Federal records are also helpful. The 1880 federal agricultural census confirms that Morris Ward, Jr. was now landless by listing him as a renter (for shares) of 22 tilled acres worth $100. It also shows that he had $5 worth of farming implements, $50 worth of livestock, and produced $150 worth of farm produce in the past year. He had two "milch cows," two "other cows," and one calf. One of these animals died, strayed, or was stolen during the previous year. He also owned 12 swine and 40 chickens that produced a paltry 50 eggs in the year. In 1879, he planted 12 acres in Indian corn and harvested 75 bushels. That same year, he also planted 6 acres in cotton, which produced 2 bales. There are unfortunately, not very many public records for Morris Ward, Jr. or members of his family during the 1880s and 1890s. One of the few shows that on March 29, 1893, Morris's daughter, Elizabeth Alice, married Boyd Gorman in Upshur County, where she would remain for the rest of her long life. Another record shows that on April 8, 1894, Morris's daughter, Maggie Inez, married Matthew E. Seay in Upshur County. (Maggie's twin sister, Maude, never married.) Soon after, the Ward family went to live near the town of Blossom in Lamar County, where on March 27, 1895, Morris Ward, Jr. remarried. His second wife was a widow named Mary L. "Mollie" (Thompson) Wilson, whose first husband, William A. Wilson, had died in 1891. On September 6, 1896 Mollie gave birth to the only child of this marriage, a boy named Charles Morris Ward. (She already had two daughters, Willie T. Wilson, born in 1877, and Ida Wilson, born in 1880, by her first husband.) In 1900, fifty-three-year-old Morris Ward, Jr. was enumerated in the federal census for Lamar County, Texas, along with second wife Mollie, age 42 (born July 1857 in Alabama), daughter Maude, age 23, son Jim, age 21, and Morris and Mollie's 3-year-old son, Charles Morris Ward, born September 6, 1896. Curiously, although the 1900 census identifies Morris Ward, Jr. as the owner of his farm, no deed record of any kind, showing him as either granter or grantee, can be found in the land transaction records of Lamar County. Interestingly, and unusually, the census shows his wife, Mollie, as co-owner of the family farm. This leaves open the possibility that the reason why no deed record can be found is because the land the couple jointly owned was either the same farm on which Mollie had resided with her first husband, W. A Wilson or had been purchased with an inheritance from her first husband. However, until or when some evidence is found to confirm either scenario, this must remain mere speculation. Mark Seay, brother-in-law of Maggie Ward Seay, said that when his father, Dan Seay, brought the family back to Texas after living for a while in Mississippi, they were urged by Morris Ward, Jr., Matthew E. Seay's father-in-law, to settle near Blossom, in Lamar County. In all probability, Dan Seay and Morris Ward, Jr. got along well together. Not only did they have grandchildren in common, both had served in the Confederate Army during the Civil War, and both had also been prisoners-of-war-Dan at Fort Delaware and Morris in New Orleans, after it had been captured by Union forces and he was taken prisoner while defending Fort Derussy, located at the confluence of the Red and Mississippi Rivers. One can imagine the two old soldiers sitting in rocking chairs on a front porch somewhere, smoking pipes or cigars, and entertaining one another with war stories. Whether that happened or not, the two men did not have a lot of time to get to know one another. Morris Ward, Jr. died about 1903, not too many years after the Dan Seay family had moved to Lamar County. According to one researcher (Edith Carter), Morris "Doc" Ward, Jr. was still living in 1902, "when Aunt Maude Ward died [during a visit to her twin sister] and was buried at Blossom [Lamar County, Texas]." It's likely he died that same year, or the next-probably at Blossom-because on December 29, 1903, his widow, Mollie, remarried. Unfortunately, if Morris Ward, Jr.'s grave ever had a marker, it is either missing or covered with earth where it cannot be seen. It all likelihood, considering the family's poverty, he never had one to begin with. As to where he is buried, the three most likely possibilities are: Old Blossom Cemetery, near Blossom; Red Oak Cemetery, near Detroit; or Evergreen Cemetery in Paris. According to family lore, following the death of his sister Maude, Jim Meeks Ward walked away from the cemetery and was never seen again. After living for some years in Los Angeles, California, apparently, he died in New Mexico, sometime before 1941. Mollie Ward's third husband was Charles H. Scroggins, a widower with two sons, with whom she was living, in Blossom, Lamar County, Texas, when the 1910 federal census was taken. Ten years later, when the 1920 census was taken, Charles and Mollie were farming in Jackson County, Oklahoma, where Mollie's married daughter Ida Renfro and her family were also then living. Unfortunately, no record of Mollie and her third husband can be found in the 1930 federal census. After her third husband died (date and place unknown) Mollie Ward Scroggins went to live with daughter Ida and her husband, Jim Renfro, who had moved sometime between 1920 and 1930 to West Texas. There, Mollie died on October 14, 1939 in the tiny Terry County community of Meadow. She was buried, however, in Evergreen Cemetery, Paris, Lamar County, Texas, perhaps where members of her birth family were buried.

Ward Family

This website copyright © 1996-2023 by Steven R. Butler, Ph.D. All rights reserved. |